Overview

Learn more about the project's general goals, theoretical background and organization.

Contents

- Introduction to the project

- Problem description

- Summary of Project Goals

- Justification and Theoretical Background

- Organization and Timeline

- Organization and Timeline

- Organization and timeline

- Outlook

- Organization

- Goal Development

- Review

First Semester

Introduction to the Project

The student-led study project ‘Adaptive Language Learning with AI-Assisted Conversational Agents’ began in Summer 2020 as part of the Cognitive Science M.Sc. study program at Universität Osnabrück. The project’s aim was to develop a conversational language learning application which emphasized group dynamics while providing minimal instruction. The project’s inception can be traced to a short proof-of-concept application facilitating individual verb tense practice. The project, then, aimed to expand upon this initial exploration of the concept with the inclusion of multiple users, additional tasks, and further support from a conversational agent or bot.

Problem Description

During an initial market research and brainstorming phase, we identified several market trends describing the most-common learning scenarios for language practice applications, as well as potential gaps which could be addressed by the proposed application, given that we planned to focus on group interaction, a conversational setting, and adaptive support via a conversational agent and/or AI. While learning environments such as Duolingo or Babbel already employ sophisticated machine learning analysis to adapt learning content to their users, we found their learning scenarios utilized gamified point-and-click dynamics which were not the planned emphasis for the application.

Likewise, conversational learning scenarios such as Andy English or Xeropan, while emphasizing the conversational learning scenario we sought, did so only for individual learners. We could not identify a language learning application which offered both a conversational, bot-supported learning scenario and negotiated interactions between multiple users. Thus, we concluded that our proposed application would address a gap in the language learning market. We looked to language learning forum applications such as HelloTalk for inspiration in negotiating group interactions, for although such applications did not employ programmatic methods to coordinate users about a common task, they demonstrated potential challenges for implementing a group learning scenario. The full assessment of available language learning applications can be found in the Software Requirements Specifications.

Summary of Project Goals

Given the results of the background research and market gap analysis phase, we concluded that an application emphasizing the following functionality requirements would provide an innovative language learning solution:

- Emphasis on group discussion rather than individual student-teacher instruction.

- Conversational learning environment rather than button-clicking exercises.

- Support from an adaptive conversational agent or AI-Assisted bot. The bot should provide language learning support and/or error correction and adapt content to user performance.

In order to facilitate the above criteria, we decided on several additional functionality/design requirements necessary to flesh-out the application specifications before beginning development.

- The application should negotiate group interaction by coordinating users around a common, language learning task.

- The application should motivate users to complete tasks by providing a narrative framework for progression. In our case, the chosen scenario is an ‘Escape Room’ setting, where users must collaborate to escape a fictional confinement.

- The application should target intermediate level language users (CEFR B1-B2) of approximately 15 years of age.

Further description of design decisions and justifications for these decisions can be found in the Design section.

Justification and Theoretical Background

The general application requirements mentioned above are supported by several didactic theories and language learning research. The decision to provide a conversational language learning scenario is supported by the notion of metaphorical user interaction scenarios, which are considered good practice in the field of interaction design. In short, a conversational setting attempts to replicate actual language use scenarios rather than imposing artificial, gamified activities such as drag-and-drop exercises. However, our decision to negotiate group interaction via shared, collaborative tasks poses a counterpoint to the goal of an ‘authentic’ language usage scenario, as user collaboration is centered around game-like activities which are admittedly not akin to real world interactions.

Nevertheless, we justify the decision to spotlight collaborative group games via the notion of ‘engagement’ important in the field of E-learning. As Franceschi (2009) explains, ‘Educational activities need to be able to engage the students in order to successfully meet the learning goal … Collaboration is a common tool used to increase student engagement.’ (p. 5). We concluded that collaborative tasks were a necessary requirement in order to ensure student engagement, although these scenarios would render our conversational setting somewhat artificial.

As implemented, the tasks posed to users are similar to the ‘drill-and-practice’ activities employed in the aforementioned proof-of-concept application, in which users are sequentially tasked with short exercises leveraging language skills in decontextualized chunks. As such, these activities model the systematic repetition learning paradigm rooted in 1940s behaviorism, which operates on the psychological concept of reinforcement (Lim et al., 2012). Drill-like activities are traditionally seen as monotonous for users. Nevertheless, our approach cannot be exhaustively explained through a behavioristic model, given that we also provide group discussion and collaboration functionality, aligning our application with a hybridized communicative approach. In short, although drill-like scenarios are traditionally monotonous for learners, we attempt to compensate for the potential artificiality of the tasks with emphasis on group collaboration and narrative contextualization.

Our decision to include a fictional, ‘escape room’ setting, although rendering the learning environment more implausible, is supported by E-learning research which suggests that fictional settings can be both motivating to students and enhance engagement. A study by Chen et al. (2018) identified narrative-based contextualization as a relevant factor for enhancing student learning, where storyline design was highlighted as a crucial application to improve authenticity of language use and improve engagement.

The narrative we chose for our application is an ‘escape room’ narrative wherein participants must collaborate on activities which effect escape from a fictional confinement. We select this puzzle solving scenario because it is assumed to be familiar to our target user and allows us to contextualize activities which require group coordination. Furthermore, the application of escape rooms in learning settings has been justified in real world contexts via educational research. As Fotaris et al. (2019) conclude: ‘… escape rooms can provide an enjoyable experience that immerses students as active participants in the learning environment’ (p. 1). Furthermore, the researchers identify escape rooms as successful in emphasizing communication and critical thinking skills during learning activities. Thus, our decision to implement an escape room narrative setting to contextualize the language learning environment is supported by the fact that narrative settings can improve learner engagement and escape rooms support group collaboration, immersion, and communication. Further description of the narrative setting can be found in the Design section.

In summary, we emphasize a conversational, task-oriented language environment because research suggests this will improve student engagement while effecting social interactions which analogize the application to authentic language usage scenarios via a communicative approach to language practice. Additionally, structuring the group interaction via a fictional escape room scenario is suggested to enhance engagement by contextualizing activities and leveraging collaborative communication. Assessment of the project outcome and user-acceptance testing can be found in the Testing section.

Organization and Timeline

The project is self-organized by student members of the study project team. During the first semester, the team was divided into three groups:

- The Implementation team is responsible for the technical side of the application by maintaining the application’s codebase and backend infrastructure. This group has documented their work and findings in the Implementation section.

- The Design team prepares application functionality mock-ups and user stories which guide the implementation’s development in line with the original requirements. This group has documented their work and findings in the Design section.

- The Testing team is responsible for both technical and user-acceptance testing to ensure the application’s performance aligns with our team’s intent. This group has documented their work and findings, including a preliminary evaluation of the application, in the Testing section.

It must be noted that these group descriptions are by no means exhaustive nor fully-descriptive of the responsibilities of the individual groups. For more complete descriptions please refer to the respective documentation sections.

Project progress was controlled with reference to a feature-based waterfall schedule which saw the sequential design and implementation of modular application features following a period of brainstorming and design. For a more complete visualization of the schedule during the first semester please refer to the Project Timeline.

Second semester

In the second semester of the project we altered our original organizational approach to foster additional idea-generation for the purposes of developing new features and addressing organizational problems which precipitated during the first semester.

Organization and Timeline

As mentioned, we faced difficulties fostering inter-group collaboration during the first semester due to the rigid tripartite structure we adopted to organize ourselves around the concept-development and startup task groups. To address these concerns and organize ourselves more thematically around specific task groups, we implemented several ‘task forces’ which rested atop the preexisting group structure and aimed to allow more-fluid communication between members devoted to the design and development of a specific application feature. The newly introduced sub-groups were determined based on the primary functional goals of the second semester and were as follows:

- Achievements. The achievements task force developed a new gamified achievement system for the application. Their work is documented in the achievements section.

- Storytelling. The storytelling task force developed a more immersive storyline for the application and developed accompanying media. Their work is documented in the storytelling section.

- Adaptive Module. The adaptive module task force developed a path selection module integration with additional data collection for adaptivity and performance evaluation. Their work is documented in the adaptive module section.

The above group concept and accompanying task groups were brainstormed in a pseudo-agile development workflow. For a more complete visualization of the project schedule during the second semester please refer to the Project Timeline.

Third semester

Typically, a study project at the University of Osnabrück has a life cycle of two semesters; as such, several changes took place between the second and third semester of the project. Most importantly, the vast majority of the people who had contributed to the project in its first two semesters moved on to other academic activities, while a new influx of members joined the project. This turnover also resulted in a change in managerial leadership, with the unofficial role of project manager being passed on to someone other than the original creator and manager of the project. As a consequence, the organization of the project during the third semester differed slightly from what had previously been done.

Organization and timeline

At its core, the team maintained the structure it had adopted during the second semester, namely:

- a basic underlying partition into three main groups (implementation, design, and testing);

- a more specific partition into “task force” groups.

The three main groups were formed based on the results of a preliminary questionnaire where prospective study project participants stated their skills and interests. Loosely speaking, team members with a programming background were encouraged to join the implementation team; those with experience in didactics, human-computer interaction or UX design were encouraged to join the design team; those with knowledge of statistics and research design were encouraged to join the testing team. This tripartition served as a starting point at the beginning of the semester and facilitated the onboarding of new team members with different areas of expertise.

By contrast, the task force groups clustered team members around specific issues or features that needed to be addressed quickly and efficiently. Interdisciplinary groups of this sort were created and disbanded all throughout the semester, as determined by the team’s new and improved agile development workflow.

The new workflow we adopted was inspired by the SCRUM framework. The main intuition of this agile workflow is to break down the work into goals that can be completed within time-boxed iterations, called sprints. After a few initial meetings of brainstorming and ideation, we determined that this semester of the project would consist of four sprints, each lasting two weeks. Each sprint was organized as follows:

- Plan: we kicked off each sprint with a meeting where we set our goals for the current sprint. When necessary, we created specific task force groups to achieve those goals;

- Deliver: over the course of two weeks, the groups would collaborate towards those goals and deliver on the expected features;

- Evaluate: at the end of each sprint, we had a meeting where we evaluated the outcome of said sprint and reflected on what to improve during the next.

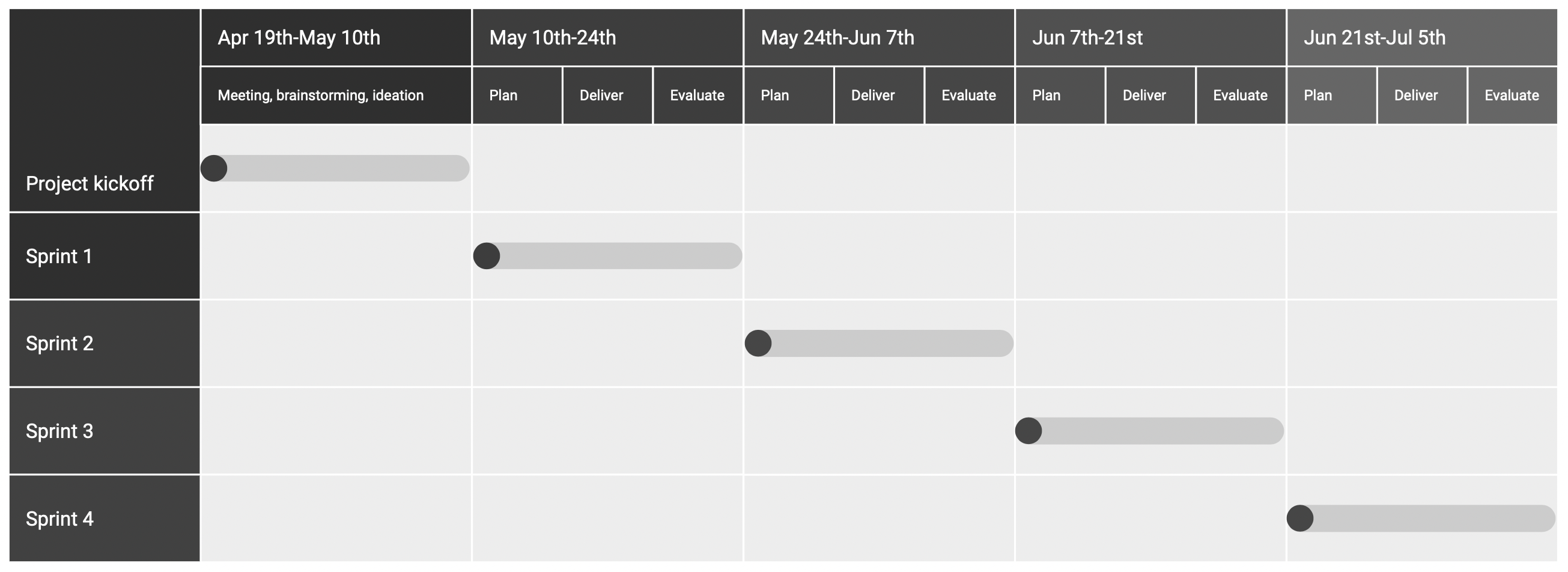

Here’s our agile development framework at a glance.

Figure 1: Our agile development framework at a glance.

It should be noted that all team activities were carried out remotely, due to the constraints caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. To facilitate remote collaboration, the team used GitHub (for coding), Slack (for instant messaging), Mural (for meetings facilitation) and Notion (as a live wiki to track overall progress).

Outlook

At the end of our final sprint, we not only evaluated the outcome of that sprint, but also of the project as a whole. Overall, the group reported generally high satisfaction levels with respect to the project, its organization, and its accomplishments. Nonetheless, a few points of potential improvement were identified:

- Going forward, the team wishes to adopt a more rigorous SCRUM approach, by electing a team member to the role of SCRUM master (separate and distinct from the role of general project manager);

- Given the voluntary nature of the project and the impossibility of imposing a clearly defined weekly workload, the team would benefit from a set of guidelines that establish best practices for communication and collaboration;

- The three basic teams (design, implementation, testing) will each elect a team leader to facilitate decision making, goal setting and team coordination;

- Remote collaboration on the project will resume even before the official lecture period begins, to facilitate a smooth transition into the new semester.

Fourth semester

In the fourth semester, the composition of the study project members changed again. Most importantly, the total number of participants decreased, since new members could only participate as interdisciplinary students and former participants finished their working phase in the project. Additionally, the role of project manager had to be passed on again. This time, the group decided on a dual project management team, a practice that is becoming more and more prevalent in industry leadership positions, too.

Organization

During this semester, the group did not continue the tripartition into design-, implementation- and testing teams for various reasons. Firstly, there is always a time lag in the working phases of the three groups. For example, the design team cannot keep designing concepts until the end of the semester, because there would be no time for the implementation team to program these concepts anymore, as well as no time for the testing team to test these features afterwards. Secondly, this semester was much more goal-driven than the last semester. That is since this was to be the final semester of the project, the group carefully elaborated on what the end state of the project should look like before the semester started. This way, the participants were then solely working on the tasks that had been planned, which made working in task-forces much more suitable than in the three overall teams. Another benefit of omitting the tripartition was the reduced time and organizational effort. Last semester, it was noted that the study project is quite meeting-intense, which left less time for the actual work on the tasks. This was because the entire group held a weekly meeting, the three main groups had a weekly meeting, and the task forces held individual meetings. Moving away from the tripartition could remove one level of organization, including its respective meetings. The reduced group size was an additional motivator for this decision. As mentioned above, the group held weekly meetings to ensure a constant workflow on the study project. The meetings were held either hybrid or fully online, depending on the corona incidence rates. We have retained the SCRUM structures created in the last semester in our meetings. This means we worked in two-week sprints, each sprint started with defining new tasks for the sprint and was closed with a review phase at the end of each sprint. To elaborate the review phase even more compared to last semester, an online feedback questionnaire was introduced, which enabled the participants to also give their feedback anonymously. The evaluation of these sprint reviews was created by F. Wollatz and can be found here. It shows, among other things, that the participants were very satisfied with the overall outcome of the study project.

Goal Development

From the beginning, it was clear that this would be the last semester of the study project. Therefore, the group had to think about what the final state of the project should look like. In order to ensure satisfactory completion of the study project, the study project members were first asked what a satisfactory end of the project looked like for them. In addition, the participants were asked what they would like to take away from the project for themselves, so on what kind of tasks they would like to work on and which skills they would like to acquire. Next, the answers were collected and categorized. The project members were then able to vote for the different categories in order to show how important they deem the different aspects for a satisfactory project end. Based on these votes, an ordered list of the key goals that the group wanted to achieve this semester was created on a Mural board. You can find this board here. The goals set are:

- No game-breaking bugs

- Update the adaptive module

- Finish already designed but not yet implemented concepts from last semester

- Putting our project on the IKW website

- Develop something new like a minigame or a lobby platform

- Create a play-through video

- User testing + app evaluation

- Publish a paper

In a next step, these goals were further defined into actual tasks and more feasible ideas.

Review

In the outlook section of last semester’s report, there are four points of potential improvement mentioned. Firstly, the group wanted to start preparing the study project before the official lecture began, in order to allow for a fast onset of the study project. This point of improvement was implemented by clearly defining the goals and tasks of the project before the lecture time. On the downside, this way the interdisciplinary participants could not take part in the overall goal-setting process, however, this proceeding has the advantage, that only students who know the study project very well and who have worked on it quite intense set its goals. In addition, knowing what tasks there will be, makes it easier for new members to decide if they want to join the project or not. Other points of improvement became obsolete with the new, smaller group and the changed organisational structures. For example, eliminating the tripartition into the design, testing and implementation team made it no longer necessary to elect team leaders for each group. The same goes for electing a Scrum Master or establishing best practice guidelines for communication and collaboration matters. As mentioned above, all the goals the study project members set at the beginning of this semester were achieved, which is reflected in the high level of satisfaction among the study project members.

Additional resources

Software Requirements Specifications

References

Chen, Z.-H & Chen, H.H.-J & Dai, W.-J. (2018). Using narrative-based contextual games to enhance language learning: A case study. Educational Technology and Society. 21. 186-198.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge, U.K: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Franceschi K., Lee R., Zanakis S., and Hinds D.. (2009). Engaging Group E-Learning in Virtual Worlds. J. Manage. Inf. Syst. 26, 1 (Number 1 / Summer 2009), 73–100.

Fotaris, Panagiotis & Mastoras, Theodoros. (2019). Escape Rooms for Learning: A Systematic Review.

Lim C.S., Tang K.N., Kor L.K. (2012). Drill and Practice in Learning (and Beyond). In: Seel N.M. (eds)

Sharp (2006). Interaction Design: Beyond Human Computer Interaction. Cornell. Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA.