Adaptive Module

Learn more about the application's adaptive module.

Overview

The adaptive module is the application’s component which provides individual users and, by extension, groups, with content which is attuned to their previous performance. Adaptivity in educational applications contributes to the uniqueness of the users’ learning experience, facilitates their learning process, and improves the learner satisfaction (Martin et al., 2020). Since our app is designed for interaction of learners in groups, the individual learning abilities of the users may differ, so keeping the tasks at the appropriate level for everyone is an especially challenging but important task. The newest version of the adaptive features can be found directly under this link, or see an overview of all the relevant sections below.

Contents

- Adaptive modules problems

- A paradigm shift to player self-regulation

- The path features

- Adaptive data

- Closing remarks

Second semester - Adaptive module weaknesses led to player self-regulation approach

The missing scientific backing and unclear justification are the adaptive modules problems

At the end of the first semester we conducted an evaluation of the adaptive module’s validity. This evaluation concluded that the module would need further development in the second semester. The reasoning behind this conclusion was that its proficiency model relied too heavily on intuitive difficulty and the module’s goal of favoring the players’ weaknesses lacked justification. In summary, the problems of the module were:

- the missing scientific backing for its positive learning impact,

- the missing scientific backing for the item difficulty classification,

- the missing justification for the prioritization of weak player categories,

- the missing of data to solve the above points.

A paradigm shift to player self-regulation neutralizes the problem

We noticed that other self-adjusting models suffer the same justification problem because the effectiveness and justification for a self-adjusting adaptive module is too dependent on the specific circumstances of its application. This meant we either had to research our model’s effectiveness ourselves or circumvent the problem otherwise.

Our solution was to accompany the self-adjusting model as it is with a model using player self-regulation to influence difficulty adaption. Now the player themselves can intervene, if the difficulty level or category prioritization are not serving their learning goals.

Despite our change of approach, we still need to prove the positive learning impact of the adaptive module. We address this need with a dedicated data collection module you can read about below and with extensive testing.

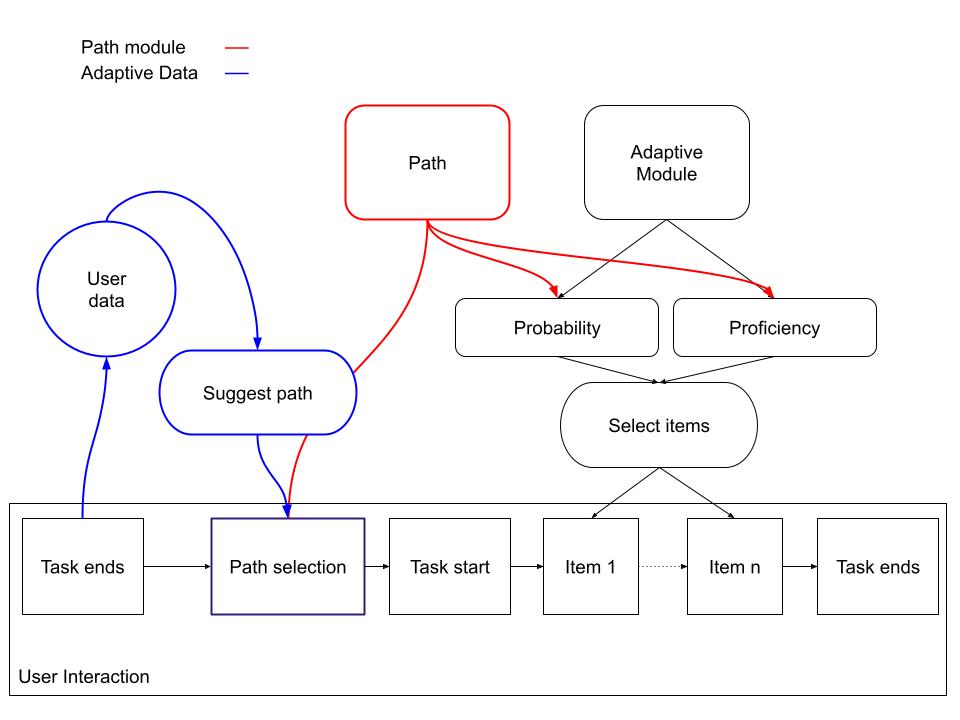

How all of this new features interact with each other and within the adaptive module you can see in the graphic below.

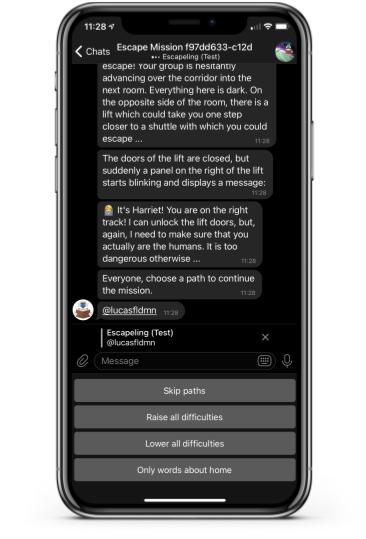

The path selection choice after each task iteration is partially data driven

The player first interacts with the path selection module after his first task. The player is asked to choose a new path to influence the further tasks. For the moment the player is provided with four options:

- increase all difficulties,

- decrease all difficulties,

- focus on a single category,

- don’t select a path,

as you can see in the screen shot below. While the first two options and the fourth are still generic, we already use collected data to choose the third option. We would like to extend this data driven approach in future versions of the module.

Each path can influence both the difficulty and the probability with which a category is chosen

Each path object consists out of a path_name, an path_id, three dictionaries prof_dict, prob_dict, conditions and a boolean set_prob variable.

The path_name and the path_id are for identifying the path type.

The dictionary prof_dict encodes the change in proficiency the path is exerting. For example the increase all difficulties path has the following dictionary: {0.1 for all proficiencies in Vocabulary or Grammar}. This means all proficiencies of the player are increased by 0.1 for this path.

The prob_dict dictionary encodes the change in probability the path is exerting. For example the focus on a single category has the following dictionary: {1 for chosen category; 0 for other categories in Vocabulary or Grammar}. This means the only category that has any probability is the chosen one.

The new process is kept totally compatible with the adaptive module

When a player chooses a path after a task, it is registered in a path list object in the student object of the player.

During task item selection a category has to be selected. Either the probability to pick a certain category is completely determined by the path. This happens, when a path has the set_prob attribute set to True. If this is the case only the last path with that property is valid and the category is chosen according to the probabilities in his prob_dict dictionary. The second case is all paths have set_prob = False. Then the probabilities of a path are added to the existing probabilities and then these probabilities are normed. This happens in their acquisition order for all paths.

Second, a difficulty is selected. The players proficiency for the selected category is added to the values of each path. The calculated proficiency is always kept under 10 or and over 0. The calculated domain specific proficiency is then balanced against the more general average proficiency.

Finally, an item out of the chosen category with the calculated difficulty is randomly selected out of the database.

Adaptive Data

To support the above-described path selection functionality and to select paths more-intelligently we needed additional user performance data.

General Approach

As outlined in the chapters devoted to the sentence correction and vocabulary guessing tasks, both activities coordinate groups of users around a sequentially-progressive task by iterating over individual users as targeted activity leaders. In this way, each iteration is associated more-heavily with a particular user and can be inferred as more relevant to their performance for the purposes of performance data collection. Given the assumption, that each iteration can be associated directly with the elected participant, we record task iteration metadata and attribute these to the selected user as a measure of his/her success with the particular task item. For example, in a sentence correction task iteration in which one user is attempting to successfully-correct an erroneous sentence with the help of other users, the total time taken to complete the iteration is assumed to be indicative of the elected user’s ability to resolve the presented sentence item and, by extension, informs suggested paths at the conclusion of all task iterations.

In the below section we describe how this data collection procedure can be conceptualized at a higher level relevant to the backend application infrastructure.

Technical Infrastructure and Further Details

The below diagram summarizes the adaptive module data collection protocol as it is integrated within the sequential task flow, with task iteration performance metadata collected during each user-association iteration before being stored to the PostgreSQL database at the end of the user’s turn. After all task iterations when the path selection options are presented, we retrieve previous user performance entries from the database and prioritize a dynamic third option based on the duration of previous task iterations associated with a specific sub-skill. In effect, that sub-skill which required the most time for a selected user to complete will determine the third option.

Closing Remarks

The aforementioned data are used primarily to inform the path selection module, but are also intended to permit future meta-analysis of user-item interaction and have already been applied to a testing strategy outside the scope of the documentation of this section. For further details of these evaluative applications please refer to the relevant documentation page.

Of final note are the next steps potentiated by these data, as it is clear that the path selection module in its current form does not take full advantage of the metadata collected, and it is likely a point of future development to, following detailed analysis of the available user performance data, expand the application’s intelligent adaptivity with more extensive requisition of the collected data.

Fourth semester - Reworking of the adaptive module

Motivation

The original adaptive module consisted of two main parts: adaptivity of the task difficulties based on user proficiency data (developed in semester one) and the self-regulatory element (developed in semester two).

In the previous semester, we noted several shortcomings of the existing module. Firstly, we think the game has low re-playability value. Escape games are usually not designed to be re-played by the same players. Our chosen gamification settings therefore implies limited interest in repeated engagement with the bot. A solution of providing a variety to the storyline has been designed - more information can be found here. However, the task data also did not contain enough variety to keep providing novel educational content over a long period of time. As such, the developed learner model would likely not receive enough user data in order to work appropriately as designed.

Secondly, as pointed out by the previous collaborators themselves, the data difficulty was labeled somewhat arbitrarily. Although there has been an attempt at mitigating this by introducing user self-regulation, the option to choose paths led to confusion and was eventually disabled, since the adaptive features were not transparent to the users. We therefore felt that the overall adaptivity level of the current version was rather low.

Lastly, although the players may have been motivated to play the game again in case of failing their mission, they did not receive sufficient feedback on their mistakes that would actually help them overcome their failures in future attempts.

As the original parts of the adaptive module had been implemented across many parts of the codebase, we realized optimizing its current functioning would be a very complex task, possibly not achievable within the remaining timeframe of the project. Moreover, it would likely not have provided the desirable improvements in the users’ perceived learning experience.

We therefore considered several directions, on which adaptive features could be implemented into the existing structure of the escape mission:

- assessment of current level of English – the aim was to gain a more accurate initial score for each user that would be fed to the existing learner model. However, we imagined that doing a proficiency test at the beginning of the mission could potentially be tedious to the users and a short or non-standardised version would be of low added value, so this idea was eventually abandoned.

- adaptivity on group level or individual level – in the original set-up, if one player made a mistake, the whole group would need to do an additional iteration; the obvious alternative is to provide feedback based on the personal learning needs of individual users.

- personalised feedback within the tasks – we thought that giving the players clearly visible and relevant feedback would significantly improve the educational value as well as decrease users’ frustration with their mistakes, and therefore improve their overall experience. According to Peirce and colleagues (2008), educational games need to prioritize their gaming experience over educational aspects in order to keep the users’ motivation high. For this reason, we also did not want to disturb the immersive nature of the game. We aimed to achieve this by using suitable emojis to indicate relevant feedback and also by integrating some feedback directly into the narrative, namely presenting the tips through the Non-Playing Character Elias – the friendly alien, who is trying to help the group escape from the spaceship.

To some extent, similar guidance had already been implemented into the discussion task in the previous semester by providing the users with some general feedback and tips regarding their grammar. The latest improvements have therefore been applied to the sentence correction and vocabulary tasks, as described in more detail below. The remaining listening task is optional and therefore left out from further work on adaptivity.

Sentence correction task

In sentence correction tasks, we have three subtasks for each sentence presented. Players have to be able to complete each of these subtasks. Only after completing each of these subtasks, it will be considered complete/passed.

In the first part, a random player first received a sentence, and they should identify whether the sentence is written correctly or not. And then they should also be able to identify the mistakes in case of a Grammatically wrong sentence. And the final part is to also be able to correct it.

Players have to have a sound knowledge of English grammar and be able to identify them and correct them as well. This complexity makes this sentence correction task a bit difficult as well and more suitable for adaptive feedback. This is why we have decided to include adaptive features in each of these steps.

At each step, a hint will be provided in such a way that players will be provided with guidance for completion of the subtasks. But we make sure that they only get enough information and not the answer itself.

Firstly, if the player is not able to identify if the presented sentence is grammatically correct or not, then they are given a hint. And the hint is followed by a thought bubble to be distinguished from other text, and not get lost in other dialogues.

With these first hints, a player can find a suggestion, so they can find which word is written incorrectly in the sentence, which is the next step in this task.

Even with the first hint, they might not be able to find the incorrect word in the given sentence. If that is the case, In the previous setup after this step, players were provided with the word which was incorrect, but were not described or told why this word was incorrect. And this would not help Players to learn from their mistake. And because of this reason, we decided to provide a second hint in the form of a link. This link will be directed to a document describing the appropriate grammar rule requirted. In this way, they can learn the grammar rule require for writing the sentence in a correct way.

The final task here now is providing the replacement(correct word) for the sentence. The player can still make a mistake while responding to this subtask. In the previous version of the game it was so that, in this case, they would fail this iteration. This makes the game look unfair to the players and not very user-friendly. The best optionis to provide a next chance if they had never seen the required grammar rule for correcting the given sentence. We decided that they would fail the iteration if they had already seen the appropriate grammar rule. And if they have never seen the appropriate grammar rule required for this sentence, then the user will first get a grammar rule and get the opportunity to correct themselves.

Vocabulary guessing task

The vocabulary guessing task aims to make the users actively use and have a full understanding of a particular word. This is achieved by making other users guess the word from the definition. The user needs to come up with a description of a word which is adapted to the other user’s knowledge. In an ideal case, the interaction between users knowing the word and those who have no or only a partial understanding will help all users to understand a piece of vocabulary better. Effectively, the users lacking knowledge use other players as learning resources as described in McGroarty (1989).

The goal of the game is to allow the users to make use of their own vocabulary knowledge. First, the user who must describe the word is allowed to get a new one, if the word is unknown. This already constitutes an adaptability feature, ensuring the user actually is feeling competent enough to explain a word to their teammates. Playing the role of an expert explaining a certain concept was proven to help settle and deepen the comprehension of said concept (Silbert et al., 2013).

Additionally, in the current version of the “Escapeling” application, a hint system was implemented. We assume that the player proceeds by a top-down approach, where they will first explain the context of the word at hand and then refine it until one teammate guesses the word correctly. It is of course not always the case that users describe the word using this pattern. But, it is a helpful assumption to guide the users throughout one round if they do not succeed with the task at hand. The hints are therefore structured in a similar way, using a top-down approach. First, after multiple wrong guesses, the application will first try to frame the users into the correct context.

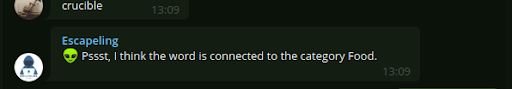

Here, the application will give the users the category of the word to be guessed. The categories were originally crafted to match the paths structure used in the previous version of the adaptive module (see Adaptive module). It was decided to modify the categories’ names in order to match a B1-B2 vocabulary level. The categories used in the current version are: free time, culture & arts, education & society, nature & science, food, body & soul and household & buildings. After three wrong guesses, the users get the word category as a hint (Figure 1).

Figure 1: After 3 wrong guesses, the category of the word is displayed as a hint.

Figure 1: After 3 wrong guesses, the category of the word is displayed as a hint.

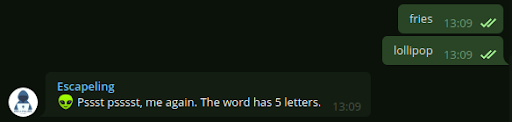

The second and third types of hints focus on the letters of the words. This allows the users to narrow down their guesses until finding the correct word.

After three additional wrong guesses, the group will receive the number of letters of the word (Figure 2). Then, after three more wrong guesses, the users will get a hint showing one letter of the word and its place within the word, similar to a hangman game (Figure 3). It should be noted that after 9 wrong guesses, when the hangman hint is shown, each additional wrong guess will trigger a supplementary hint. The supplementary hint will show an additional letter inside the word, but no more half of the letter will be shown.

Figure 2: After 6 wrong guesses, the number of letters is revealed.

Figure 2: After 6 wrong guesses, the number of letters is revealed.

Figure 3: After 9 wrong guesses or more, a hangman-style hint is displayed. The total amount of different letters shown does not exceed half of the the total number of letters in the word.

Figure 3: After 9 wrong guesses or more, a hangman-style hint is displayed. The total amount of different letters shown does not exceed half of the the total number of letters in the word.

Possible extensions and improvements

The adaptive module in its current form was designed as a minimal viable feature. It should put into practice the decision of changing the objectives of the adaptive module. In addition, it highlights the choices made concerning learning and user experience. These choices have been supported by the interviewees during the first qualitative evaluation. More details about the evaluation can be found at (see Evaluation). Therefore, we assume the design choices we made are the correct basis for future theoretical improvements the application could profit from.

Future features should therefore also target specific aspects of the user’s abilities, i.e. identify their weaknesses and address them. All feedback must be targeted and help the user to enable them to understand or solve the task. It must also avoid repeating information the user already has, in order to maximize the efficiency of the learning progress.

Improvements on feedback and adaptability can theoretically be applied to all four tasks. An additional adaptivity feature could be used to foster a helpful inter-user support system which overall improves the learning experience as suggested by McGroarty (1989). In the sentence correction task, each round consists of three subtasks, namely recognizing the correctness of the sentence, identifying the faulty word and producing the correct word instead. Instead of having a single student perform all those tasks when performing poorly, the subtask could be divided amongst the students. This would make use of the other students as resources, allowing the student to make profit of the knowledge of others. In conclusion, new adaptability features require often to modify the tasks’ flow, but overall improve learning efficiency.

Bibliography

Martin, F., Chen, Y., Moore, R. L., & Westine, C. D. (2020). Systematic review of adaptive learning research designs, context, strategies, and technologies from 2009 to 2018. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(4), 1903-1929.

McGroarty, M. (1992). Cooperative learning: The benefits for content-area teaching. The multicultural classroom: Readings for content-area teachers, 58-69.

Peirce, N., Conlan, O., & Wade, V. (2008). Adaptive educational games: Providing non-invasive personalised learning experiences. In 2008 second IEEE international conference on digital game and intelligent toy enhanced learning (pp. 28-35). IEEE.

Silbert, B. I., Lam, S. J. P., Henderson, R. D., & Lake, F. R. (2013). Students as teachers. The Medical Journal of Australia, 199(11), 757. DOI:10.5694/mja13.11353