Testing

Learn more about the project's testing strategy.

Note: This page contains several sections, each describing testing information relevant to a different semester of the project. Escapeling’s testing process has naturally evolved over time, and the information contained on this page is a testament to that. To facilitate navigation, here is an overview of this page’s content.

Contents

- Test Strategy

- Usability Test

- Technical Testing

- Prospects For The Next Semester

- References

- Introduction

- Methods

- Quantitative Analysis

- Qualitative Analysis

- Conclusions

- Resources

- References

- Introduction

- Literature

- Testing Performance

- Technical Testing and Bug Reports

- User Acceptance Testing

- Evaluation

- Results

- Recommendations

- References

- Motivation & Evaluation Plan

- ESL Student Interviews

- Interview Structure

- Results

- User Tests @ Uni Osnabrück

- Test Structure

- Results

- Summary of Results

First Semester

Contents

- Test Strategy

- Usability Test

- Technical Testing

- Prospects For The Next Semester

- References

Test Strategy

The testing strategy we designed was inspired by the paper A Software Testing Primer (Jenkins, 2008). In the paper, Jenkins differentiates between two goals of software testing: verification and validation. A test can either verify that the specified requirements are fulfilled or validate that the application design serves the purpose of the application. As both goals come with their own methodology, we split our testing strategy along this line. One part of our group conducted a technical test to verify the implementation while the other conducted a usability test in order to validate the usefulness of the application as a group learning scenario for the English language. The usability test was further divided into performance and satisfaction subparts.

Usability Test

The below section describes the usability testing strategy and results.

Usability Test Strategy Overview

When testing usability, we aimed to find a testing group resembling the target audience as closely as possible, i.e. schoolchildren in the ages of 14 to 17 with English knowledge between pre-intermediate and upper-intermediate. Our initial idea was to remotely recruit 15 to 25 testers from a group of language course students who almost perfectly matched our ideal testing/target group. Given that no further adjustments between sessions were planned based on the intermediary results, the data from a testing group of this size more than sufficed to assess the application’s usability.

Testers received two instruction sets, one with a short overview of our work and software/hardware requirements, distributed a few days before the test, and the other with the test instructions themselves, e.g. “Join the game” or “Play the error correction game”, distributed immediately before the test. To minimize misunderstanding, the second instruction set was accompanied by a short video session where testers could receive further necessary explanations to a degree that would not bias their testing activity. The testers were also asked to share their screen recordings with the test’s facilitator.

The initial step of the usability test was a background questionnaire gathering information about testers’ age, English learning experience, computer literacy, previous e-learning experiences, etc., generating information to match a tester against our target audience.

The next step was the performance test. A common practice in usability testing is to assess the application’s performance based on its effectiveness and efficiency. However, choosing appropriate metrics to estimate them in a learning task presented a challenge because not all common approaches would have worked in a reasonable way. For example, a learning task’s goal is to transfer knowledge, even if it requires extra processing effort and delays from the user, it is therefore irrelevant how quick the user is with the task, provided they learn from it.

Diah et al. (2010) previously encountered the same issue with their learning application and chose success rate, defined as the proportion of successful trials to the total amount of trials, as their basic metric. We decided to use this approach in our usability tests as well and defined success and partial success criteria for the application’s two tasks, being worth 1 or 0.5 points respectively. In the sentence correction task success required three out of four users in the game room interacting throughout the task session and partial success was defined as two out of four active users interacting in the session. Success in the word guessing task was defined as at least one description posted, followed by an incorrect guess and further description or by a correct guess, partial success was defined as a description followed by a guess posted. Though rough, success rate provides a general picture and answers the essential question of whether the users can even manage the required task. Its seeming sketchiness is also compensated for by low cost and straightforward interpretation.

The second measure employed to test the application’s performance was the error count. It is calculated as the number of times users performed erroneous actions per task session, such as giving out their secret word in the word guessing tasks or unnecessarily using the buttons/Telegram API. The error count shows,if the users are misguided by the application’s flow and instructions and how far their understanding of the application agrees our intentions.

The usability test was concluded with a satisfaction questionnaire that contained questions about the user’s experience overall and with the separate tasks, their willingness to recommend such an application to their friend and basic understanding of the tasks’ goals. Both the opening and closing questionnaires were distributed via Google Forms.

Evaluation

After the guidance and instructions had been provided to the testing group and a video Q&A session conducted, the usability test began. As a first step, participants were asked to fill in the pre-questionnaire to collect some information about the testing group, including their background and experience in learning foreign languages with the help of apps or e-learning platforms and their experience using Telegram. Then participants, following the instructions, played two rounds of each game (“Sentence Correction” and “Vocabulary guessing”) in the Escapeling app. Testers made screen recordings and provided us with them. Screen recordings were used in order to evaluate the results afterwards. Finally, participants had to fill in the post-questionnaire to evaluate the tasks and rate the app in terms of their satisfaction with the tasks and the Escapeling app in general and their willingness to use this app for further collaborative English language learning.

As Escapeling is designed for collaborative English learning, the tasks are supposed to be played in a group of four people. Participants have the common goal to solve the task and escape the room. Therefore they are allowed to communicate with each other in the group chat, contribute to the task success and thereby help each other progress learning the foreign language. We recruited two groups of four people to conduct the test.

Examining the results of the pre-questionnaire, we extracted the following information about testers: our test groups consists of high school students being 14-18 years old. Concerning their English level, the pre-questionnaire has shown that 42.9 % of testers have upper-intermediate level of English, 28.6 % have intermediate level, and 28.6 % pre-intermediate level. The majority of the group has prior-experience in using Telegram. The majority of participants have used various language-learning apps before as well, e.g. Duolingo, Reword, Drops, HelloTalk, and PuzzleEnglish. Furthermore, 71.4 % of testers have shown their interest in using the app for collaborative language learning.

Concerning performance results, we conducted two test sessions. For session one, performance could not be objectively measured because the app crashed during testing. Hence, we have taken into consideration only results of the second session for evaluation of user acceptance. To evaluate the success rate we calculated the proportion of completed successfully to the total amount of attempts.

The success rate of the first task was 8.0/8.0 = 1.0. During the first task (“Error correction”) participants were asked to play twice (such that each participant had his/her turn twice). During the test all participants made a guess, whether the sentence was correct or not, tried to find the mistake in the sentence and correct it. So that, the success rate in the first round is 1.0, and in the second round 1.0 as well. In total equaling 2.0. Success rate in the second task was 8.0/8.0 = 1.0. During the second task (“Vocabulary guessing”) participants were asked to play two rounds again, so everyone had their turn twice. This task was completed successfully. All participants posted the description of the provided word, all of them made at least one guess and the task was completed. The error count was 2.0. The most common error occurred during the second task naming the shown word to the other participants, as this violates the instructions.

Examining the results above, we can conclude that performance results are quite good. The results of the post-questionnaire confirm that as well. Participants were highly satisfied with the app and both tasks. The majority of the group would highly recommend this app to their friends. Based on the tests, the application was accepted by the target user and mostly met the requirements that have been set initially.

Outlook

An important point that we have seen during the test procedure is that it became obvious that participants barely communicated with each other in the group chat, most of the time they were waiting for the messages and instructions from the bot. When they experienced some difficulties to give the correct answer, they were working individually. As the initial idea of the app was collaborative learning, some reminders and encouraging messages from the bot, when the silence in the chat lasts too long, might be helpful to engage users to interact more with each other, as they have a common goal while completing the task. This additional functionality will also help users to practice the language in a more natural way, communicating with their peers.

Another possible improvement to the application’s usability is clearly indicating when it crashes. Throughout the tests, not seeing whether the bot is still running sometimes caused misunderstanding, as the users were expecting a reaction that was impossible because the bot was offline. This could be implemented by simply sending an explicit error message when errors occur.

Concluding the usability tests, we should note that one of the biggest usability issues was possibly not the application’s design, but Telegram’s API commands employed to run tasks and arrange people into game rooms. The users, especially those who had no prior experience with Telegram bots, got confused easily and struggled to continue when they needed to employ a bot command. We should possibly consider wrapping them into buttons or providing extensive instructions on how to operate them (e.g. pin the message with the instructions in the chat). It will make the interface of our chatbot more user-friendly and will help players remember how to use the bot.

Technical Test

The below section summarizes the technical testing strategy and results.

Overview

The goal of a technical software test is to detect the defects or bugs that a software exhibits before it is released. Defects in this context are deviations from the behavior specified in the software’s requirements. The task of a technical software test is to design and execute routines that reveal as many of the software’s defects as possible.

In technical software testing the standard procedure is to analyze the software in its planning stage. The goal is to detect components, that will exhibit defective behavior and will need improvement later on in the process. This is necessary, as software testing is the last step in software production prior to release. This means it is not possible to wait until the software is implemented to design the software tests.

A common way to arrive at a test strategy is to

- Analyze the important and vulnerable components of the software as dimensions.

- Think about possible and likely errors that might occur in each dimension.

- Define test cases, that cover as many dimensions and errors as possible.

- Create test instructions instantiating the test cases.

In our project we kept to this industry standard, as it is a straight forward way to detect the most important error, is easy to implement for people not acquainted with software testing, is easy to analyze afterwards and easy to communicate to other parts of the team.

Test Dimensions

The first step of this strategy is to analyze the software and detect important and vulnerable parts of the software as software dimensions. Typical categories, that help detecting software dimensions are functionality, code structure, user interface elements, internal and external interfaces, the input and output space, the data, the environment and use case scenarios. Important for us were the functionality in form of the technical specifications, the code structure as communicated by the development team, the environment in form of Telegram and different operating systems, and the use case of a group learning scenario. We did not test the data structure or internal and external interfaces, as our project is still rather small and lacks a complicated data structure or internal and external interfaces.

The dimensions we identified were:

- Group handling functionality

- AI adaption

- Sentence production

- Operating systems (Windows, Android)

- Telegram UI

- Requirement functionalities of the two tasks

Test Cases

While the test dimensions span the space of defects, that might occur in a software that test cases try to cover this space. Ideally one would create a test case for every conceivable error that can occur in a software. This is impossible. First, because it is presumptuous to think that the identified dimensions or created test cases cover all errors and second, because testing has limits as i.e. time constraints. The task in test case selection is thus to create and select test cases, that cover the error space ideally, meaning in such a way, that all major and as many errors as possible are detected in the software test.

A test case consists out of a description of what part of the error space it tries to cover, how it tries to achieve this and what is needed in order to do so. In our case the test cases contained following information:

- Involved software modules

- Tested requirements

- Test case description including test goals and procedure

- Step-by-step instructions for the test case

- Conditions which must be met to realize the test case

- Data required for the test case

- Expected result

Test Instructions

The test instructions are derived from the test cases such that the software testing can be conducted with them. Rather than being a one-to-one mapping of test cases, test instructions can cover multiple test cases or a test case can be divided between several test instructions. Nevertheless the test instructions are created in such a way that all selected test cases are covered and thus the test space is covered as well. Test instructions utilized in the project include:

- A group handling test, trying to detect defects during the creation and management of the bots group creation and group joining, as well as the task start-up

- A combined UI and task progress handling test, that required playing the tasks of the application to their end and detecting any defect within the task flow or the Telegram UI elements

- A difficulty adaption test, verifying, that the difficulty adaption module does work as specified in the requirements

- A sentence handling test, trying to detect defects with the message handler during the tasks execution

Defects

All defects that we detected were reported in a table containing the following dimensions:

- Summary of the defect

- Detailed description of what happened

- Instructions on how to replicate the defect

- Expected behavior of the application

- Actual behavior of the application

- Attachments and additional remarks

- Severity of the defect for the application

The severity of a defect was decided by a simple matrix which had a value of zero or one for the two dimensions frequency and impact. The defect was treated of low severity if both dimension were of value zero, of medium if one dimension was of value one, and high if both had a value of one. For each defect a corresponding GitHub issue was created. This issue was then used by the development team to fix the defect. This issue contained the same information as the defect table entry of the defect.

Results

After conducting the tests we detected approximately 15 defects, some of them were very similar or even the same defect occurring on a different setup. As a software test should detect all possible mistakes of a software, we were surprised by the small quantity. For a future test we want to optimize our approach, analyzing why we detected so few defects. This is of special importance to us because the usability test revealed that we missed some defects which negatively impacted the usability tests. Nevertheless, we can conclude that we tested a solidly build software being a good basis for the further improvement of our project. Based on the results of the work done by our group, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Positive

- Conducting technical testing allows us to detect defects and bugs of the program and helps to prevent their occurrence in future development.

- The use of freely distributed products makes it possible to use technologies for remote interaction of subjects of the educational process among all interested users.

- The idea of remote interaction of all participants in the educational process, laid in the basis of the project, allows to reduce the time spent on staying in special institutions, which is especially important for additional improvement of language skills.

- Additional acquisition of skills in working with computer and electronic communication technologies by users.

- Optimization in volume and significant improvement in the quality of educational and methodological materials through the use of electronic media and constant updating of information.

- More effective use of technical and organizational capabilities for the implementation of a flexible individual approach to training.

Negative

- The lack of a stable high-speed Internet leads to high time costs to ensure effective remote interaction.

- Incomplete provision of the necessary computer skills by users, which can lead to disruption of the task.

- At this stage, for constant remote interaction, a specialist observer is required who can restore the process when a technical error is detected.

Prospects For The Second Semester

Users of mobile devices can choose from thousands of programs that allow them to learn new languages, including applications designed for audio listening, entire foreign language courses, and even applications with online chat functionality where people can try their communication in English at a new level.

The idea behind the project is unique and the overall goal is to provide a user-friendly application for collaborative group activities. At the moment, the application is already a fairly high-quality product with many useful functions, but it still needs improvement. According to analysis of the usability test survey, participants showed an increase in the interest in receiving remote communication services. We below summarize some concluding thoughts on the project’s successes, shortcomings, and potential next steps.

Successes

- stimulating interest and enhancing the cognitive and communicative activity of students in the mainstream of the educational process;

- formation and development of communication skills on the Telegram platform;

- language acquisition.

Shortcomings

- Participants hardly communicate with each other but prefer to do everything on their own;

- Difficulties in using the built-in commands and functions of the API Telegram.

Next steps and Opportunities

- Study, analysis, and application of didactic capabilities, properties, and functions of Telegram;

- Development of a model for remote interaction of all participants;

- Selection, organization, and structuring of the content of instructions in conjunction with the application;

- Development of requirements for the creation of tasks;

- Study of the psychological characteristics of the interaction of all subjects of the educational process in conditions of distance interaction;

- Development of pedagogical technologies (adding the learning side of the project);

- Methodology for organizing feedback and consultations for application users;

- Solving problems of assessment and control in group learning.

In general, all the tasks set during the projects’ meetings were achieved. There is no doubt that there is still room for improvement. The development of distance technologies in education is rapidly becoming popular. As a result, it can be noted that all listed possible improvements for distance group learning give an effect not only individually, but also together, which allows us to speak of the application as a qualitatively new form of education.

References

Diah, N. M., Ismail, M., Ahmad, S., & Dahari, M. K. (2010). Usability testing for educational computer game using observation method. 2010 International Conference on Information Retrieval & Knowledge Management (CAMP).

Jenkins, N. (2008). A Software Testing Primer: An Introduction to Software Testing.

Nielsen Norman Group. Why You Only Need to Test with 5 Users. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/why-you-only-need-to-test-with-5-users/

Tullis, T., & Albert, B. (2013). Measuring the user experience collecting, analyzing, and presenting usability metrics. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier.

Second Semester

Contents

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results

- Conclusions

- Recommendations For Coming Semester

- References

Introduction

Software testing is the process of analyzing a software tool and related documentation to identify defects and improve product quality. Due to the fact that software testing becomes part of the programming stage, developers have the opportunity to fix bugs already at the initial stage of development. This reduces the risk of defects in the finished product. It is important to find bugs or weaknesses at the initial level, and the earlier the process begins, the easier it will be to make changes to the overall structure of the application. Continuing the work of the testing group, we followed a similar strategy. But with some differences. In this semester we divided our strategy into two main dimensions: Technical Testing and User Acceptance Testing.

Methods: Technical Testing

Technical testing of this and last semester followed a test case-based testing strategy - a formalized approach in which testing is performed based on pre-prepared test cases, test case sets, and other documentation. This method also allows you to achieve maximum completeness of the application research due to the strict systematization of the process. A well-written test case allows you to store information for long-term use and exchange of experience between testers and teams. Thanks to this, we were able to complete unfinished test cases from the last semester without any further questions. This proves once again the importance of correct technical documentation.

As mentioned above, the term “test case” can refer to the formal recording of a test case in the form of a technical document. This record has a generally accepted structure, the components of which are called test case attributes. Below is an example of one of the test cases we wrote (Pic.1)

Picture 1 “Test Case Collection” example.

Along with the tests that were written in the last semester, but were not conducted, we wrote new test cases that relate to the new features of the application: 1) a new adaptive module 2) achievements 3) a third task “Discussion”. The new third task developed this semester was tested only at the User Acceptance Testing phase, because the preliminary version of the assignment was made only by the end of the semester. The third task requires the creation of new test cases and the corresponding testing. Testing of new application functions was carried out on specially created special branches of the code (discussion_task branch), which, after a certain number of tests, will be added to the main application code.

With testing on the Telegram API, there is always a question of which accounts to use for the quality of experiments. For this, as in the last semester, our course was provided with special testing Telegram accounts. All necessary data can be obtained from course tutors or responsible testers.

Methods: User Acceptance Testing

Acceptance Testing - formalized testing aimed at checking the application from the point of view of the end-user and making a decision on whether the customer accepts the work from the project team.

In this section, we will explain the general principles of this type of testing and the following strategy. In the next sections, you can find more accurate data about the group of end-users (testing participants) and results.

The first stage of testing is a formal explanation to the group of participants the purposes of this testing, especially explaining to them that it is not their knowledge that is being tested, but the quality of our product. Along with this, the subjects are given minimal instructions for how to interact with the bot for the first time. The second important step is to collect information about users so that it might be possible to correctly organize groups by interest, age, and level of knowledge (Pic.2). This information also provides importance for future data analyzes.

Picture 2 Pre-Test Questionnaire

This testing also carried another function - to check whether the application helps to improve their language skills with consistent use. Initially, the testing requirement was a daily interaction of at least 30 minutes for 2 weeks. However, missed meetings were also allowed, but no more than 2 times a week. After the completion of two weeks, participants must pass a post-test survey to assess the quality of the product and the experience gained, where they can also leave their feedback on any of the parties to the project (Pic.3).

Picture 3 Post-Test Questionnaire

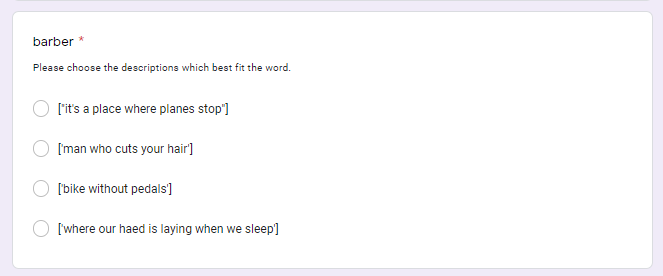

The final step is to pass the so-called quiz, specially compiled on the logs of their answers and the answers of other participants (Pic.4).

Picture 4 “Proficiency Quiz” Example

Personalized Learning Outcome Post-Tests

To gauge if the application has affected individual user’s language skills we employ a learning outcome post-test strategy involving personalized langauge skill assessments. As mentioned in the Adaptive Data section, the application periodically collects various user performance metadata which are used both to adjust application difficulty and to inform the aforementioned learning outcome post-test. Given the application’s adaptive learning strategy, it is difficult to design a post-test of language skill which can assumedly be compared across all participants in a controlled manner. In light of this, we use the performance metadata to automatically generate personalized skill assessments which aim to, for each participant, test whether items which proved particularly challenging during application use can be successfully answered.

For example, the sentence correction task is scored according to the number of task iteration phases which are successfully passed. This allows us to rank users’ task iterations by their retrospective challenge, assuming that task iterations with lower scores were more challenging for a student. We then present these task items to the student during the learning outcome post-test. Likewise, we also present customized post-test tasks for the vocabulary guessing task, incorporating user-generated descriptions to achieve a matching task following the methodology of Vesselinov (2012). The image below shows an example of such generated vocabulary matching questions.

Results: User Acceptance Testing

The below sections document the analysis and results from the aforementioned user acceptance tests.

Test Group Descriptive Statistics

We were starting off with eight students in our testing group, but three of them left after a short amount of time. The five remaining participants were all second language learners. The age of the students was very homogenous, one participant was 13 years old while the all other ones were 14. Accordingly, they were visiting either the seventh or eight grade in school. They all defined their language level as B1- intermediate and therefore met the lower boundaries of our target group, which we defined as either B1 or B2 learners. In terms of relevant applications, only one actually had experience with what we would generally define as learning apps, namely Doulingo, Lingualeo and Skyeng. One other user already used a dictionary website as learning support. Regarding language exchange applications, only one of the students already experienced this type of language learning. All participants apart from one already had experience with Telegram, which is fortunate as this is the basis of our application and would therefore allow low barriers. Luckily, all of the users answered that they were interested in using an English learning app for collaborative studying.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Although test group size and testing phase duration are limited so as to constrain the power of any qualitative analysis, we can still derive insights which facilitate an improved understanding of the user-application interaction and suggest avenues for further development which will likely improve the application’s usability.

Superficial investigation of the backend proficiency values used to attune task item selection to student performance validate the adaptive module’s approach to gradually adjust task item difficulty. Given that proficiency values increase and decrease relative to student performance, we can observe these values to bootstrap an inference regarding the learning outcomes of the test group and the operation of the adaptive module. Looking at the overall distribution of final test-period proficiency values irrespective of sub-type, we find a trend towards values greater than 5. Given that all proficiency values are initialized at 5 and increase or decrease depending on performance, this result validates the operation of the adaptive module when cross-referenced with the moving average of the presented task item difficulties (shown below) over the testing period, which shows a positive trend towards higher difficulty (R2 0.48).

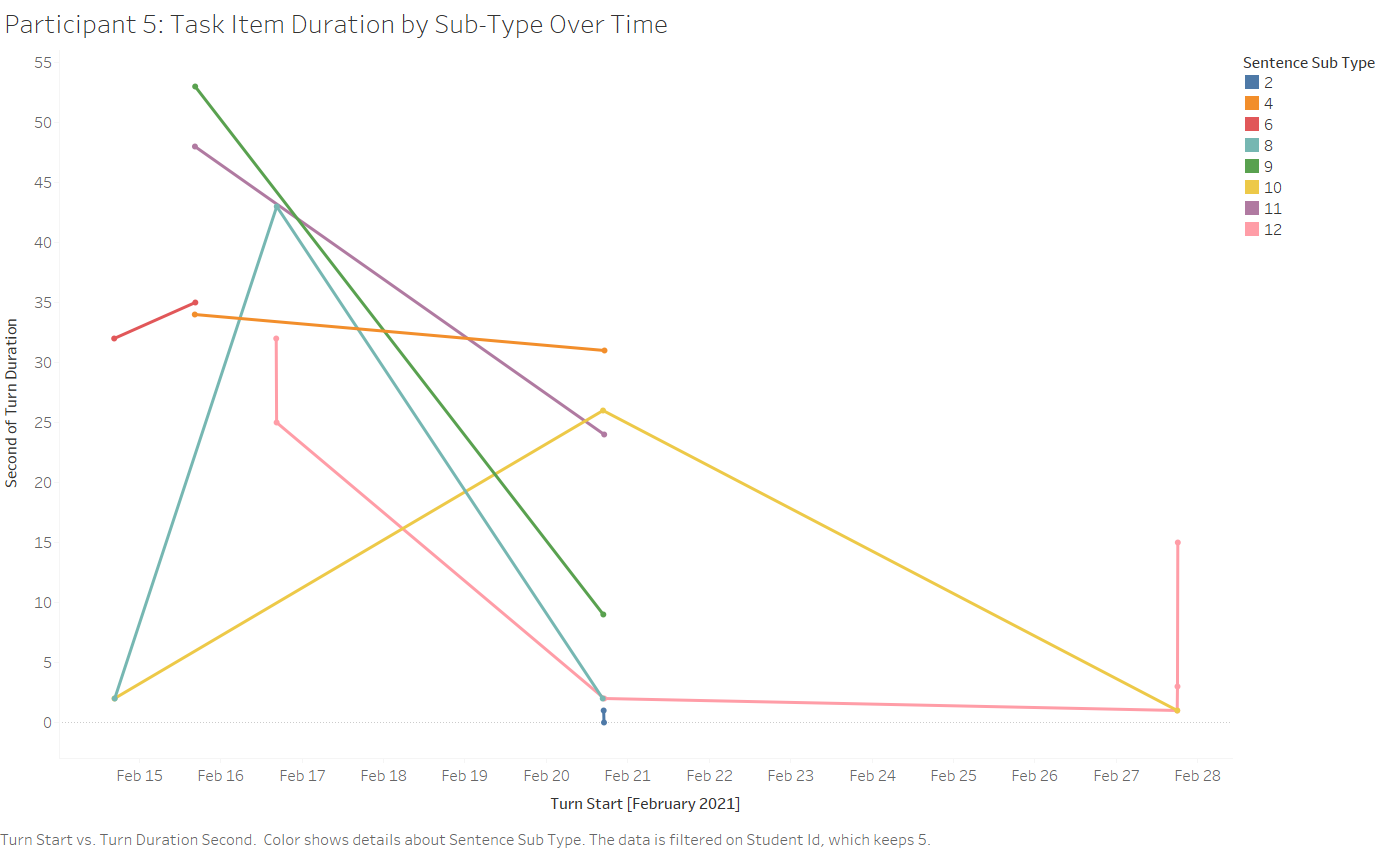

Additionally, given that we track user performance vis-à-vis various task-specific data points, by visualizing these performance metrics over time we can intuit the behavior of the adaptive module relative to user performance. The figure below shows sentence correction task data for one user during the test period, with each unique data point representing a single task iteration, where task items sharing a grammatical sub-type are connected by color-coded lines.

This graph makes clear the relative duration of task items over time for this student, demonstrating that many task item sub-types, for example, sub-type 12 (subjunctive, pink line) first require significantly more time than by the end of the testing phase, suggesting that the user was able to improve their performance with this sub-type as measured by task duration. This single-user case study also suggests an avenue for further development, namely that a user be able to focus on a subset of sub-types in order to demonstrate proficiency improvements before moving onto other types of task items. While this user was presented with a variety of task sub-types via the adaptive module, allowing the user to selectively focus on only a few sub-types may improve learning outcomes for selected sub-types.

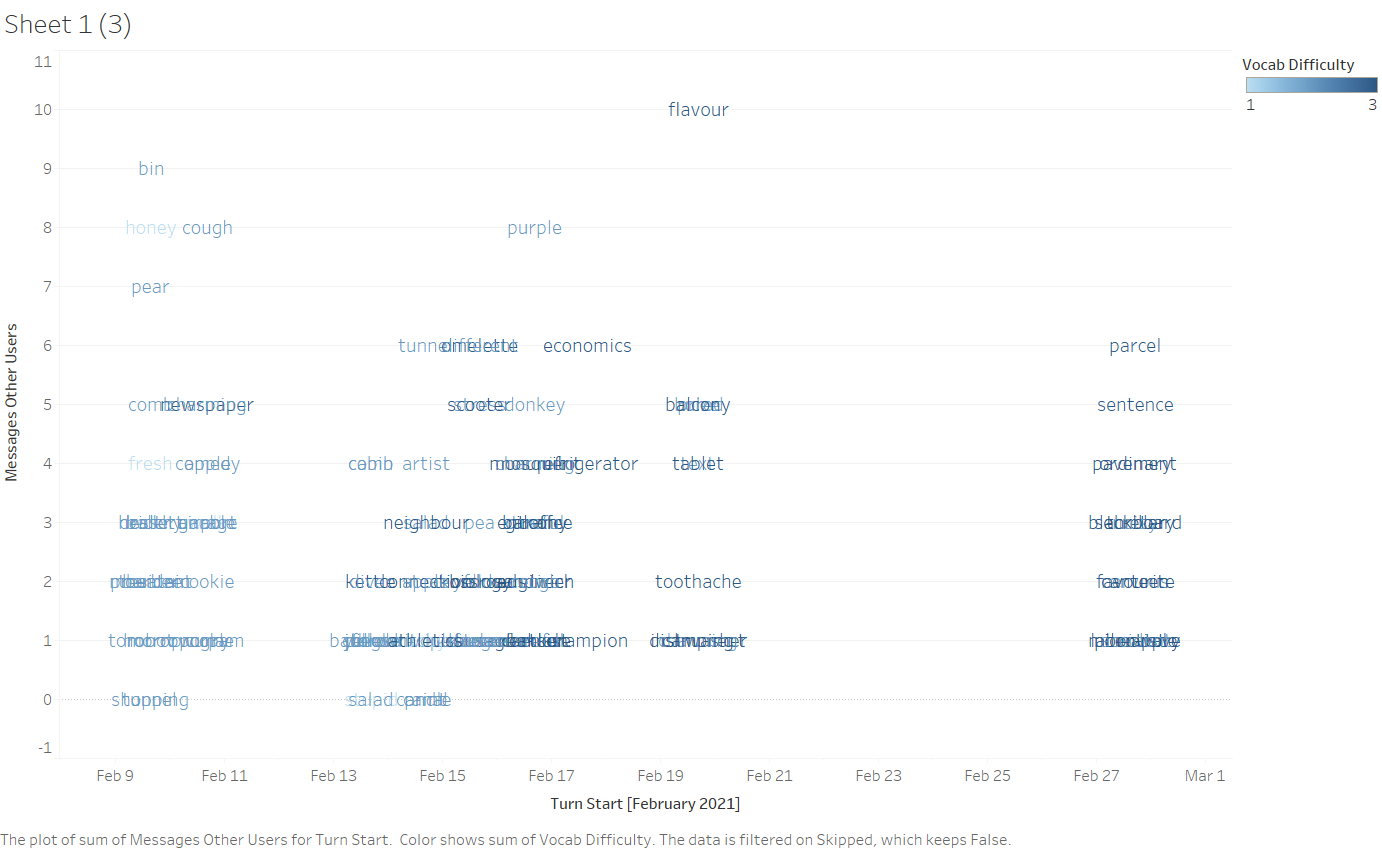

Regarding the vocabulary guessing task, by visualizing the number of messages sent by non-elected users (i.e., the number of guesses) for words of each task iteration, we can identify those words which proved particularly-challenging for this test group to correctly guess or explain.

Nevertheless, it may be the case that words which required relatively more guesses do not correlate with our difficulty assumptions informing the adaptive module, therefore compromising the application’s user model and implying that additional attention to user performance may be valuable to properly attune task selection to user proficiency. When visualizing expected word difficulty as determined by neural network classification against number of guesses, we find that many words of expectedly low difficulty required relatively more guesses, and vice-versa. Given that the number of guesses is not incorporated into the adaptive module computations, which presently only consider the correct/incorrect status of a given task iteration, these data suggest that the adaptive module’s ability to suggest appropriately-challenging task items could be improved by integrating the number of guesses as a relevant data source.

Of final note are the aforementioned learning outcome post-tests, which are bespoke to each student based on previously-missed items. For a set of post-tests comprised of 20 questions each (10 sentence correction, 10 vocabulary matching), the median error rate is 1/20, ranging from 1/20 to 0/20. Although extremely limited, this result suggests that participants could make some learning progress relative to questions which were previously-challenging. It may be that the functionality for retrieving previous questions is more valuable to application features emphasizing spaced-repetition learning, which suggest one avenue for future development.

For additional visualizations and data not mentioned in this section, please refer to the resources below.

Qualitative Data Analysis

We asked the learners to provide us some feedback on their experience with the application overall as well as with the individual tasks. Therefore we gave them the opportunity to fill out a questionnaire regarding their usage of the application.

The first task, concerning sentence correction, was overall rated at a 6.75/10 by the users. While they liked the idea of the task, they would have wished the examples to be more fitting to what they already learned in school, for example more tasks concerning verb forms. When they hadn’t encountered a certain grammatical form in school yet, it seemed to be challenging to even complete this task. But apart from that, the learning progress they achieved by mastering the complex task was mentioned as a positive point.

The second task, vocabulary guessing was rated at a 10/10. Accordingly, the feedback was exclusively positive. The focus group enjoyed the experienced autonomy and collaboration as well as the learning of new words. While the learners marked the task being quite easy as a positive point, it might be a take-away to enhance the difficulty to improve the learning process.

The third task, discussion, was rated at a 6.5/10 by the learners. The feedback we gained was mostly focused on the high difficulty of the task for the learners and the need for confidence to participate in the discussion. Apart from that, they appreciated the opportunity to strengthen their language proficiency of this task as it was, in their opinion, the most challenging one.

We specifically asked the users for their feedback on the newly displayed achievements, since this was a new feature we added this semester. The overall response was very positive, with the users seeing this as a fun feature to keep track of their achieved goals. On the other hand, one user felt like the propose of the achievements was not entirely clear to them. This might result from the times of testing being some days apart, so that the users were not able to actually develop a streak. Nonetheless it might be interesting to keep in mind.

The overall feedback from the users was in general very positive. The students did not only seem to enjoy the usage of the application, but also saw potential in future developments.

Based on these useful remark, we can take multiple ideas into the future development of the application. First off, we should consider to adapt the difficulty of the tasks more to the actual proficiency of the specific user, as the vocabulary guessing seemed to be quite easy while the other two seemed quite challenging. Additionally it might be important to include more explanation on the achievement module.

Conclusions

Although our evaluations remain limited by the total number of participants, we were able to expand upon our previous semester’s test methodologies with more quantitative data sources reflecting user performance, while also receiving additional valuable feedback which will help to improve the application. Notably, it is clear that further attention to application difficulty is needed, particularly the apparent simplicity of the vocabulary guessing task. Some application bugs still persist which can disrupt user experience. Finally, investigation of user performance presents several avenues for future feature development.

Recommendations for Coming Semester

From the above analyses and discussion we derive several recommendations valuable to coming project iterations:

- Allow users to focus on a subset of task sub-types by improving the persistence of the path selection module.

- Integrate the number of vocabulary guessing task iterations guesses as a relevant variable used to adapt task difficulty.

- Repurpose the automated post-test generation logic for additional application features involving spaced-repetition.

- Attend to the difficulty of the sentence correction and vocabulary guessing task items to handle a broader range of user proficiencies.

Resources

Final Test Proficiency Distribution for Each Subtype

References

Vesselinov, R., & Grego, J. (2012). Duolingo effectiveness study. City University of New York, USA, 1-25

Third Semester

Contents

- Introduction

- Literature

- Testing Performance

- Technical Testing and Bug Reports

- User Acceptance Testing

- Evaluation

- Results

- Recommendations

- References

Testing Semester 3

INTRODUCTION

Since the Escapeling project develops many new features, testing is constantly in progress, adopting the appropriate strategies to verify the quality of the added changes. In this chapter, you will learn about the concept, organization, and results of our testing framework in the third semester of the project.

LITERATURE

For the correct operation and analysis of the test materials, initially, the project team studied all provided training materials and existing methodology on testing, described in the previous chapters. Our strategy adheres to some of the basic principles outlined in Jenkins’ work [1]. Based on the review of the material, we divided our work into Validation and Verification. Validation testing is also known as dynamic testing, in which we ensure that we have developed a product correctly in terms of design. Most often, it is this approach of testing that includes working with potential users and various surveys. Verification, also known as static testing, allows us to check whether we are developing the right product or not. It also checks whether the developed application meets all the requirements specified at the root of our project. Furthermore, previously collected results from the second semester’s User Acceptance Testing were studied.

TESTING PERFORMANCE

The purpose of this section is to discuss all of our activities during the semester, as well as the main ideas and limitations of testing as part of software testing.

TECHNICAL TESTING / VERIFICATION

The organization of the verification and test management activities should be closely related to the preliminary design. For this, a general testing strategy is initially formulated, including test methods, documentation forms, and test evaluation criteria. In addition, a test schedule is drawn up with specific feature development. At the same time, a documenting basis was established to ensure the quality of the test documentation. Weekly, all team members attended our joint meetings where we were aimed at studing the basic principles of testing, Q/A discussions, and further development. In addition to organizing testing and creating test cases, which collect all information on tested features, the project itself should be analyzed and checked for bugs. Session simulation can be used for testing the properties of the system structures, design, and the interactions of subsystems. Our implementation team should use step-by-step design instructions to verify the consistency and logical structure of the system, while the design review should be performed by the testing team.

USER ACCEPTANCE TESTING / VALIDATION

Test data should be created to validate the main aspects of the Escapeling introduced during the design process, as well as test materials based on the structure of the system. Thus, as software evolves, a more efficient set of test materials is created.

This semester has made a valuable impact on the functionality and quality of the application. Since last semester testing efforts were aimed at estimating the impact of our application on users’ English knowledge, we decided to continue working with participants from previous semesters and conduct a survey on how they like our application improvements.

When testing the usability of the changes made to the application, we turned to the participants of past tests, since they are as close as possible to the target users. It is worth noting that some of the changes made were formed precisely on their feedback and grades from the second semester. Since the adaptive module has barely changed, it was decided that there was no need to test the impact of repetitive sessions.

EVALUATION

Initially, we planned to have a simulated session with a trial to complete the “escape” and then ask our participants to fill a satisfaction questionnaire, however, at some point, our group couldn’t run the bot due to some technical errors and it was decided to provide our participants with a different way of demonstration.

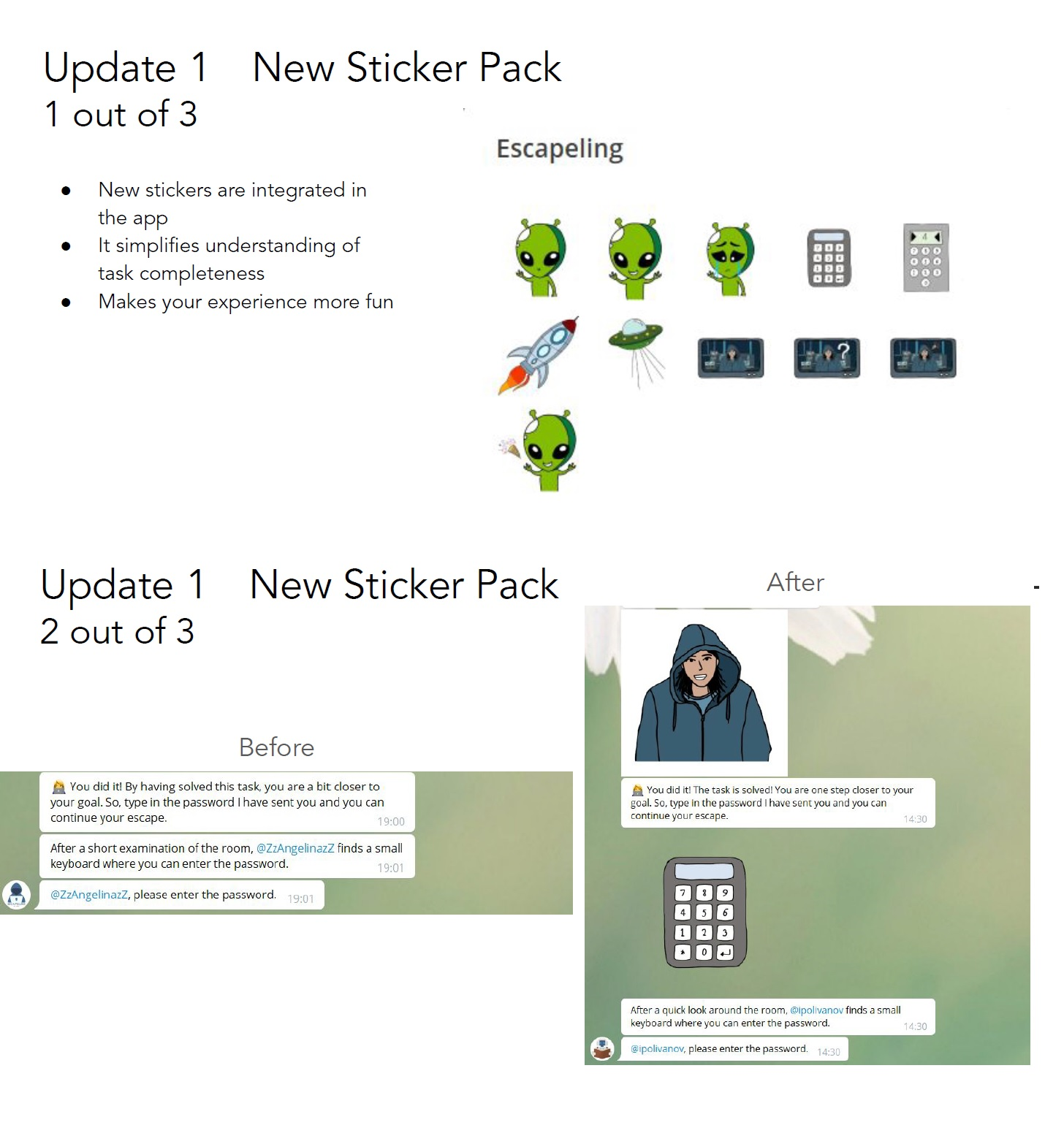

Testers received two sets of material: a) PDF file with examples of modified application functions collected in presentation style (adaptive graphics, message formulation, new task, etc.) and b) a feedback questionnaire. A PDF file consists of a total of 15 slides of 6 updates (New Sticker Pack, Simplified Text Messages, Getting Ready Step, Approval Gifs, Discussion Task Update, New Task - Listening) that illustrate and describe main differences (Pic.1).

Picture 1 PDF-slide example

The usability testing concludes with a feedback questionnaire that included questions about the quality of the changes in general and their satisfaction with the improvements. All questionnaires were distributed via Google Forms. First, participants should find and select their username from a list. Second, they should fill a questionnaire for every update that consists of three questions (Pic.2):

- How do you like this improvement? Rated by a 10-point scale.

- The goal of this question is to estimate how users like the very concept of this update.

- How much does this improvement help the application performance? Rated by a 10-point scale.

- The purpose of this question is to estimate how users rate the quality of performance of this change in our application.

- Your thoughts/feedback. Free writing.

Picture 2 Update 1 - Feedback Questionnaire

For Update 6 they also received an additional block with a task goal and a description so it would be clear for the participants how the task works.

RESULTS

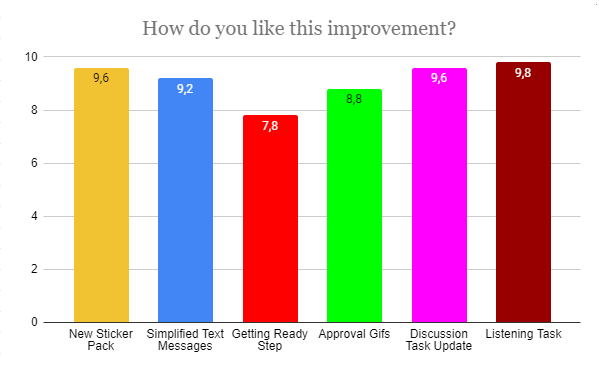

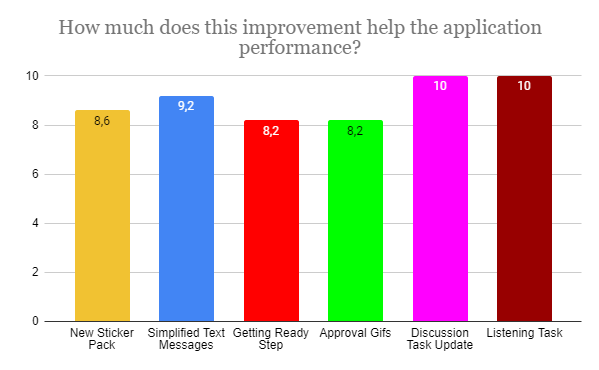

The first update concerning the addition of the new stickers was rated by the users with an average of 9.6 points for an idea and 8.6 for the performance. Furthermore, according to their personal feedback, we can say that adding stickers was a great idea, but still one of the participants showed caution in the amount of their use:

“I enjoy new design, I like when studying is fun. However, it might appear to me that there could be too much of them. I guess it can take some space from my device memory but still I can simply clean the history :) “.

They also liked the idea of simplifying texting along with the integration of stickers. So they rated “Simplified Text Messages” at 9.2 for both the idea and the implementation. From past research, it has been noted that the volume of messages is difficult for the children to comprehend, so this supplement was presumed to be successful. But besides this, the comment of one of the participants was noted as a negative point:

“I still feel confused with messages”.

The third update that our participants analyzed was the addition of visual effects when users confirm their participation in the session. The results of this survey indicated that not everyone considers this addition to be necessary in terms of performance and perception. The average scores were: 7.9 for the idea and 8.2 for the implementation.

The addition of GIF files to the various sections of the application was the most successful update of the Escapeling bot, based on the questionnaire results. Although one of the participants gave a rather low score of 4 and 3, in the commentary he did not indicate the reason, but rather also emphasized that this update looks “in principle, cool”. The rest of the reviews were overwhelmingly positive.

The focus group liked the addition of special identifiers for the remaining time in the third task. Almost everyone indicated that they had missed it earlier.

“Cool update immediately clear how much time is left to complete”.

The average scores for the idea and the performance for this update were 9.6 and 10 accordingly. It is the second best rating among updates.

Finally, our survey ends with an assessment of the new Listening task. Perhaps one of the most important results for the “listening task task force”. All users gave an extremely positive score of 9.8 for the idea and 10 for the application. One of the participants said:

“listening tasks are very helpful in developing English and speaking easily in the future”.

Overall, user reviews were very positive to all the additions. Children not only enjoyed using the app in the past, but they were able to see the development of the app. To check all average scores see: Picture 3 and Picture 4.

Picture 3 Average Satisfaction Score by update

Picture 4 Average Performance Score by update

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR COMING SEMESTER

- User Acceptance Testing. Since the project, presumably, comes to its end next semester, we recommend to conduct the last User Acceptance Testing with participants who are completely unfamiliar with our application and are probably unfamiliar with the Telegram platform. We expect it to be a good demonstration of the quality of the design and interface for users unfamiliar with Telegram.

- Bug fixes. All bugs must be fixed at the right time for the project to be considered complete. Accordingly, before the usability testing stage, there should be no errors left.

- UAT participants. Finding participants to test has always been difficult. If students from the language centre will be considered for the role of participants, we strongly advise the future project members to find them and arrange upcoming sessions as early as possible.

- New features. Some of the implemented features were not tested because of the time constrains (e.g. Discussion Task - NLP feature).

REFERENCES

Jenkins, N. (2008). A Software Testing Primer: An Introduction to Software Testing.

Fourth Semester

Contents

- Motivation & Evaluation Plan

- ESL Student Interviews

- Interview Structure

- Results

- User Tests @ Uni Osnabrück

- Test Structure

- Results

- Summary of Results

Motivation & Evaluation Plan

To evaluate the improvements of Escapeling implemented in the fourth semester of the project, our original plan was to conduct classroom testing with schoolchildren, so as to test the app with users of target age and proficiency. To this end, the children were supposed to receive tablets with preinstalled Telegram from the school. However, we had no other choice but to change our plan due to COVID-19 because the target school was closed before the children received the tablets. Therefore, we came up with two alternative evaluation possibilities which address two main aspects of the Escapeling developments: the pedagogical value and the user experience of the app. The structure of the evaluations was also guided by the data requirements for the paper submitted to the Learning Ideas Conference.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with ESL-teachers-in-training at the University of Osnabrück to estimate the pedagogical value of Escapeling in a German secondary school setting. Additionally, we conducted user tests with Cognitive Science students and students from related fields who came from the same university to collect more user feedback. We think that these evaluations are a viable alternative to the field classroom setting, even though the average age of the participants is higher than our target user groups. All participants participated voluntarily and were not reimbursed.

ESL Student Interviews

Interview Structure

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 3 university students who study ESL education at the University of Osnabrück: Mia, Hannah, Sofia (for data protection reasons, these are pseudonyms). The interviews contained questions surrounding five major themes: target audience, contexts of application, gamification and visualization, adaptability, and potential improvements. As all of them are being trained to become ESL teachers in Germany, the results in this evaluation reflect the use of Escapeling when applied to the German school system.

Results

Target audience

When the interviewees were asked which age group and proficiency group would benefit most from playing Escapeling, all of them agreed that the difficulty of the tasks in Escapeling is suitable for students in their 10th grade or above. Hannah and Mia also suggested that in the vocabulary guessing task, if the words chosen are at an appropriate level, the game can also be played with 6th graders.

Contexts of Application

All interviewees reported that they would not use Escapeling as the main teaching tool but might use it as a supplementary tool. They also suggested that it might be a good idea to enable teachers to access the data on how the students perform in this game. Teachers would then know in which particular areas students are weaker so that they can address these areas in class. Also, all of them emphasized the entertaining aspect of Escapeling, though it should not be used for formal assessment.

Gamification and visualization

All interviewees described Escapeling as an enjoyable game. Mia was particularly impressed by the colourful and lively visuals in Escapeling, as suggested that they would also be appealing to younger learners. Sofia commented that the up-to-date GIFs and memes in Escapeling could enable young learners to connect English learning and their daily life, “they sometimes also know the GIFs. I think it would be a great motivational force to be like ‘oh yeah, It’s fun. It’s [not just] learning, but also entertaining.’”

Adaptability

One of the main features of Escapeling is that the difficulty of the tasks is constantly modified to suit the English proficiency of the learners so that the effectiveness of learning can be maximized. Sofia praised the hints giving system in the vocabulary guessing game, and she commented that “giving out cues is really important […] from a didactic point of view. Statements are not given at the beginning, but they are slowly represented. I think they are great points.”

Potential improvements

Overall, all interviewees suggested that flexibility in Escapeling for teachers to choose their own materials would make it pedagogically more valuable, as Hannah and Mia suggested that if it could be linked to the English lessons in the classroom, Escapeling would become a more complementary tool in the existing English subject curriculum. For example, Mia suggested that it would be good if the teacher can decide on the discussion topic concerning a newspaper article studied in the class for the discussion task.

User Tests at Uni Osnabrück

In the final evaluation round, we recruited students of Cognitive Science and related fields at the University of Osnabrück instead of recruiting secondary school students for the reasons explained above. The goal of this testing was to further evaluate the end-user experience with our bot.

Test Structure

To this end, participants were invited to play the game and fill out a short online questionnaire. They received an email through private contacts and an email sent to the Cognitive Science mailing lists. This email linked to the bot, the lobby platform and the online questionnaire, explaining how to find a group, enter the game and asking to fill out the questionnaire upon completing the game.

Participants responded to the evaluation questions via free typing, multiple-choice or 5-point Likert-scale ratings. Participants answered questions about the pedagogical value of the different tasks, their enjoyment of the single tasks and the game overall, the UX value of the visualizations and whether they would play the game again and recommend it to other English learners. They could also optionally provide some demographic information.

Results

Data from 14 participants were collected (71% Osnabrück University Cognitive Science students, average English proficiency: B2-C1, average age: 22.7 years).

78% of participants reported that they would recommend the app to other English learners, and more than 90% would likely play the game again. On average, they indicated that they could best improve their general communication, reading and listening skills with Escapeling. The new lobby platform was rated with 3.3 average points. Furthermore, participants stated that the improved visualizations were very important for their enjoyment of the game, providing an average score of 4.3. Finally, they reported high satisfaction with Escapeling compared to other educational apps they used, providing an average score of 4.3.

Summary of Results

Overall, these results indicate the success of the UX and learning experience improvements introduced in the third and fourth semesters of the study project. The interview results as well as the high enjoyability ratings from the user questionnaires confirm the efficacy of including visualizations, improving the storyline and enhancing the user experience overall. The interviewee’s statements about the adaptability of the bot indicate the success of the learning experience improvements. Given these results, we think that the final version of the bot contributes a valuable proof of concept for a gamified AI-powered collaborative language learning application.