Vocabulary guessing task

Learn more about the vocabulary guessing task.

Contents

Design Process

The aim for the first task of the study project was to create an exercise which combined discussing and working together in a group of users with revising linguistic structures in English for learners at an intermediate language level. Once again it should be highlighted that the application is targeted on the need for learners to supplement the English lessons they get in school and not to give concrete instructions and new lessons about certain topics.

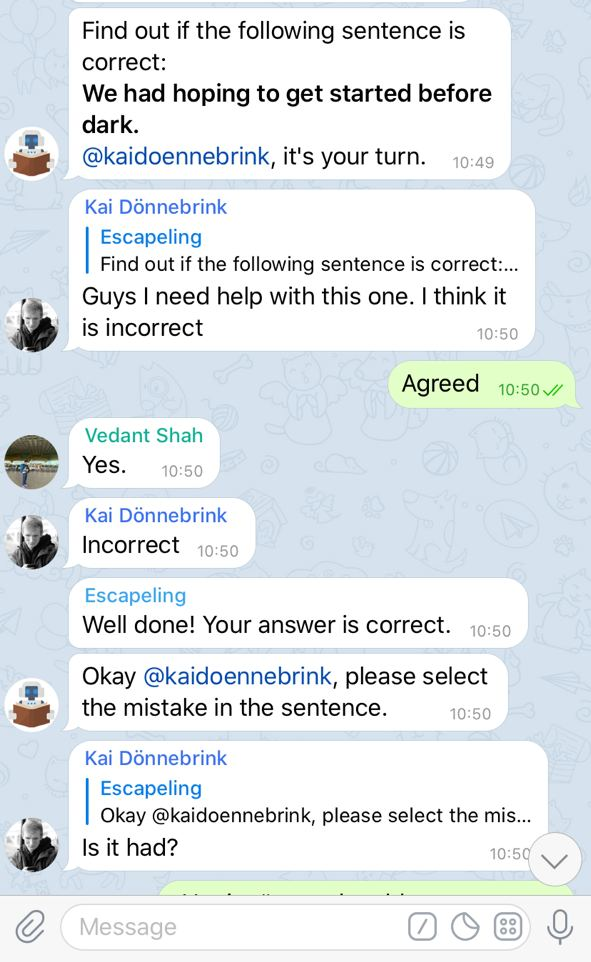

So, task 1 was decided to be a sentence error correction task. In this rather technical task, one user is chosen by the bot to take a turn, which concentrates on one sentence, displayed in the chat for all users. The turn consists of firstly deciding whether the sentence is correct or incorrect and secondly, in the case of an incorrect sentence, picking the incorrect word and providing the correct alternative for it.

The idea of this type of a primarily grammar-focused task was developed out of the wish for a task which concentrates on sentence construction. As the principle of error correction by the teacher in language learning is controversially discussed (Pawlak 2014, p. 149) but a proficient learner should be able to distinguish between correct and incorrect sentences, for example while revising their own texts, we decided to integrate a form of peer-correction with the last responsibility nevertheless in one user. So, the cooperative set-up in this task is introduced by giving the group of users the opportunity to discuss their thoughts on the given sentence and possible errors and asking questions in case of difficulties while completing the task.

Figure 1: Example of cooperation in task 1

Peer-correction “actively involves learners in the learning and teaching process” (Balderas et al. 2018, p. 184) and has been shown to be an effective method for the improvement of a learner’s writing skills (Balderas et al. 2018, p. 184). This is what we also hope to achieve with the first task which should provide a space for discussion about the sentences in question. However, the responsibility for giving an answer was decided to be given to one user on the one hand for reasons of better coordination and avoiding chaos and on the other hand to make sure to include each user in the exercise.

Only the last instance to supervise is the bot, which corresponds to the belief in learners of the greater value of teacher feedback (Pawlak 2014, p. 149) and should give the final result and confirmation. This kind of monitoring the results of the users – who are after one successful round rewarded with a part of a password to get to the next room – should frame the interaction in the chat and encourage all users to learn from it. In addition to this, the positive feedback for successfully completed turns should work as positive reinforcement for each user.

Another point to notice about task 1 is the fact that it does not contain any explicit naming of grammar structures. The idea behind this is the training through the input of English sentences which can be seen at the edge of the use of automated explicit knowledge and implicit knowledge, pointed out by Ellis et al. (Ellis 2009, p. 342). As mentioned, it should supplement English lessons in the classroom and be a practice to strengthen the English skills.

For the concrete construction of the task, a corpus of sentences served as a source. The SCoRE Corpus of Remedial English provided sentences that are written by native English speakers, additionally annotated with grammatical categories and three difficulty levels (Chujo et al. 2015). Although this corpus does not contain errors, we chose it because it came closest to fitting our needs. We then subtracted often used sentence structures from the corpus and included them into our task to make it possible for the users to learn from example sentences by native speakers. In this way, one can understand the task as well as providing input in the target language and presenting a certain pattern that learners can pick up for their own use and understanding of the English language. The grammatical categories we chose for this purpose were adverbs, gerunds, negation, present perfect, relative clauses, subjunctive, to-infinitive, verb + preposition and verb + to-infintive.

The construction of the errors per grammatical category was then achieved by replacing the words in question in the sentence structures by alternative words which would make the sentence wrong but still point out a specific structure when corrected. One example for this would be “*She never stopped love him”, instead of loving.

For the difficulty levels of the application’s adaptive difficulty model, we simply used the predefined levels from the SCoRE corpus, while making sure that the level is appropriate for our target users by checking random sample sentences of the corpus. We decided to annotate the difficulty measure of this task with “grammar”, as the focus is on sentence structuresand more fine-grained with grammar categories for which we also used the annotations of the corpus as a basis. Of course, on cannot separate the somewhat artificial grammar-category of our difficulty model from “vocabulary”, which could also be learned and revised in this task.

The narrative to introduce users to the setting of the application and to task 1 in a following step is a science fiction story taking place in space. The users are kidnapped by an alien and try to escape from the space ship they are currently kept in. This kind of narrative and escape scenario combined with the group setting should serve as a motivation in the sense of cooperative learning: Achieving a common goal, creating positive interdependence, being able to support each other and facing a common threat are factors that should contribute to a positive learning process (Dörnyei et al. 1999, pp. 164-165).

During the creation of task 1, we reached some limitations and problems that we solved with respect to time and resource constraints but that could still be improved. The sentence correction task should give room for discussions as the overall idea of the application is establishing remote collaborative learning. This has been shown not to be used much by users, so the interaction guided by the bot could point more into that direction and invite users to discuss. The construction of errors could be more naturally based on often committed mistakes by learners which was only partly possible for us to construct in the given time and setting. Other tasks focussing on grammar topics important for the target group should be added which also focus on building sentences, not only revising them.

Implementation Process

General information about the overarching task framework of our application can be found on the implementation page. In sum, the vocabulary guessing task is a subclass of SequentialTask(Task), which in turn is a subclass of the abstract base class Task(ABC).

Similar to the SentenceCorrection class, the VocabularyDescription class also inherits from SequentialTask and selects the word to be described for the selected user based on their proficiency with the call of select_word().

In contrast to the sentence correction task, answers will only be evaluated by non-selected users. However, to prevent cheating, if the self.selected_user mentions the word itself in their description, they will receive a warning through the call of get_word_warning().

Additionally, to increase difficulty, we implemented a time constraint for this task. Upon start, set_time_reminders() will initiate the reminders that will be sent to the group regularly by the call of get_time_info().

References

Balderas, I. and Guillén Cuamatzi, P. (2018). Self and Peer Correction to Improve College Students’ Writing Skills. In Profile: Issues Teachers’ Professional Development 20(2) (pp. 179-194). https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v20n2.67095

Chujo, K., Oghigian, K. and Akasegawa, S. (2015). A corpus and grammatical browsing system for remedial EFL learners. In A. Leńko-Szymańska and A. Boulton (eds.), Multiple Affordances of Language Corpora for Data-driven Learning (pp. 109-128). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Dörnyei, Z. and Malderez, A. (1999). The role of group dynamics in foreign language learning and teaching. In J. Arnold (ed.). Affect in Language Teaching. Cambridge University Press (pp. 155-169).

Ellis, R. et al. (2009). Implicit and Explicit Knowledge inSecond Language Learning, Testing and Teaching. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Pawlak, M. (2014). Error Correction in the Foreign Language Classroom. Reconsidering the Issues. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.