Discussion task

Learn more about the discussion task.

Contents

- Introduction

- Task flow

- Theoretical framework

- Materials

- Completion metrics

- Outlook

Design process

Motivation

In review of the intermediate results from semester one of the study project, we decided to design and implement one additional task during the second semester, which includes a number of aspects to complement the first two tasks and approaches the aim of the group application further.

Our goals for the application include tasks which benefit from group learning and encourage English communication between learners which is essential for practicing language skills. Therefore, for this task we want to focus on language production and writing skills, as the first two tasks don’t necessarily require users to write in whole sentences.

Finally, resulting from what was observed in the first semester, the goal is to allow for more direct and natural communication of the users instead of a sequential task pattern. Interaction between the individuals should inspire discussions among users in English and help them practice and advance their skills together. For these reasons, the aim for the third task is to stimulate and to guide a discussion between users concerning a certain topic.

As progress in communicative competence of the learners is the main requested outcome of this third task, the Communicative Approach to language learning, also called Communicative Language Teaching or Functional Approach (Jin, 2008), served as the basis for the design and the idea of the discussion task. An important aspect of the Communicative Approach is the focus on meaning in contrast to structure (Jin, 2008). Learners are emboldened to interact with each other, for example, in dialogues in order to fulfil a task. One important aspect of the task in this framework is, therefore, the function and not the accuracy of language (Jin, 2008). The developed linguistic skills within this functional dynamic can then be recalled by the learners in situations requiring similar abilities with a higher likelihood (Barson, 1993). Another important aspect of communication is, nevertheless, correctly using grammatical structures. Therefore, based on the results of previous semesters, in semester three of the project we added an additional learning goal to the discussion task: The users are encouraged to practice some important grammatical rules and are also provided qualitative feedback regarding their language.

The input for the discussion task is a short text with information about a specific topic in different areas which serves as a departure point for content-based language learning. The main idea thereby is to use language as a medium rather than explicitly study it (Lyster, 2018). These areas cover different domains which were already used for the vocabulary subskill categorization during the vocabulary task. After this short input, the users are invited to discuss the topic, guided by three questions.

Task Flow

In the first step, the reading material is presented to the users in a short text. On the one hand, the goal of the text input is to give an introduction to a topic which users might not have been in contact with yet, and offer background knowledge for the discussion. On the other hand, the text supports the learner’s context-related vocabulary. This way, English learners are already presented with example uses of words and phrases. Additionally, vocabulary learning from context may not be more efficient, but more permanent and stable and is central to most everyday learning settings (Sternberg, 1987). The introductory text is explicitly short to be easily read from a telegram chat and not to be overwhelming for the learners.

Subsequently, a first discussion question is presented to the users. These questions allow for different opinions on the topic and should stimulate the exchange of these. After a time limit is reached, the completion criteria for the task will be updated and the users will be provided intermediate feedback on their performance. Then, the next question will be prompted to view the topic from another angle. This procedure continues in a loop until the third question is reached. Having multiple questions allows users who might have problems to answer one of them to contribute more in another question. Final feedback on users’ participation closes the discussion task.

Theoretical framework

A great number of existing studies have appraised the role played by discussion tasks in second/foreign language acquisition. In the introduction to this section, we explained the motivations and intentions that led us to develop a discussion task. We wanted to build a space for our users to interact more freely among each other, and prior research suggests that group discussion relaxes the stress on the learners because the focus is not on getting a specific target exercise right, but rather on communicating more generally (Puspitasari, 2016). Naturally, a number of specific design choices had to be made when deciding how to tailor a discussion task to our specific learning environment. In this section we will review the literature that informed each of these choices.

As already noted, we wanted this task to enhance language production skills. Discussions are a staple of classroom teaching, not only in the context of second language learning. They provide opportunities to produce language in contextualized and purposeful ways: learners can practice applying form (e.g., grammar, vocabulary) and function (e.g., language used to clarify, explain, argue) to communicate and build ideas. Moreover, learners benefit from redundancy of ideas and the vocabulary associated with them: discussion allows for multiple opportunities to hear new concepts and content continuously explained, analyzed, and interpreted. Furthermore, discussions via written communication have been likened to the immersive experience of studying abroad (Oliva & Pollastrini, 1995), notoriously effective for language learning.

A number of authors have recognized that group discussions are facilitated by an online learning environment. “Electronic communication”, as it used to be called, has been integrated into the second language classroom ever since the 1980s (Warschauer, 1996). Most relevant for us, several studies and reports have indicated that computer-assisted classroom discussions are great equalizers of student participation (Beauvois, 1992; Kelm, 1992; Kern, 1995; Sullivan & Pratt, 1996). Among the recognized merits of online discussions, we find that it lowers the affective filter associated with student production (Beauvois, 1997), that it improves motivation (Oliva & Pollastrini, 1995), and that it favors greater syntactic complexity (Kern, 1995), compared to in-person discussions.

The inclusion of an initial text prompt is meant to address one of the shortcomings of group discussions pointed out in the literature, namely that insufficient content knowledge is a key issue which inhibits students’ active participation (Han, 2007). The text prompts are meant to bring users up to speed on the core ideas of the topic under discussion, creating a pool of shared knowledge which the users can then collectively build upon.

The inclusion of guiding follow-up questions is meant to frame the bot as a discussion facilitator: effective discussion facilitation is one of the key skills required for teachers who want to conduct fruitful discussions in class (Finn & Schrodt, 2016). This is in line with the framework of Guided Participation (Rogoff, 1990) where students socially interact with their peers with guidance from a teacher (in this case, the bot). The guiding questions are also meant to steer the discussion in stimulating and engaging directions, thus avoiding quick stagnation in the opinion exchanging process.

A final key point in the implementation of a discussion task for our learning environment is deciding when and how a discussion can be considered “complete”. This is strictly related to the issue of user performance evaluation. A general overview of our evaluation approach is given in the “Completion metrics” section of this page. This approach was substantially revisited during the third semester of the project; for this reason, we believed it deserved its own page under the newly introduced Learning experience section of our site. Therefore, greater details are provided in the Grammatical Error Correction page.

Materials

Given the framework we designed described above, there are two types of data required for the discussion task: texts, that should be informative and interesting enough to spark a discussion, as well as follow-up questions based on the given texts.

As the first step, we defined nine different categories which can serve as guidelines for collecting texts: Body and soul; Free time; Home and building; Humanities; Nature and science; Society; Technology; Alignment; Economy. Each text should then be a subtopic of one of the stated above categories.

Since our application is a Telegram chatbot, we assume it will be used mainly by phone users, which provides a series of other issues that we have to take into consideration. First of all, the size of a phone screen is relatively small and does not allow for sharing big texts with the users. Secondly, even if this problem can potentially be solved by presenting text in form of an image, we want to avoid situations in which users loose access to the chatroom every time they open the picture. Therefore, it was decided to present texts as messages. The ideal size of the text to be sent to the users was then determined to be maximally 120 words.

The data was collected from different Internet sources. The sources varied from Wikipedia pages to blog posts, articles in online magazines and materials posted on online platforms for English courses see Excel sheet with all relevant information provided. Our next step was to select a small excerpt from the discovered source that should be of the stated size.

Our second step was to review these texts and check if all of them meet the following criteria:

- Is this text interesting enough to spark a discussion?

- Does this text allow for sharing different opinions? Besides, the texts should be appropriate for our target group and grammatically correct. In total, 37 texts were collected.

Since our chatbot should be able to provide users with tasks of different difficulty (namely, levels 1, 2 and 3), our next task was to rate the texts according to the levels of their proficiency. This could be achieved in two different ways: via automatic evaluation and self-evaluation, based on the information provided in the scientific literature. The automatic text analyzer by roadtogrammar.com determines the text difficulty according to CEFR levels, not only by looking at average word and sentence length, but also by comparing each word to a list of the 10,000 most frequent English words. This is relevant for evaluating language complexity of the found texts. The more frequent words are presented in the text, the less difficult this text is rated to be. On the contrary, the text evaluation we performed by hand was based on the idea that criteria, used by the text analyzer, are only surface features of text complexity and are limited in their capacity to predict text difficulty. These features should be taken into account in combination with the deeper features (ideation, organisation, structure, representational models) and reader’s characteristics (background knowledge, motivation and goals of engagement in reading). For example, text difficulty is often dependent on the genre, with non-fiction texts usually presenting more challenges to the readers (Murphy, 2013).

Having combined both these attitudes towards text evaluation, we ended up dividing all texts according to three language proficiency levels that we focus on in this chatbot.

Further, the next step was to provide texts with three different questions each. Our goal was to avoid questions on text comprehension, but find those that can encourage users to share their thoughts and opinions. Below you can see an example, illustrating questions we came up with for the text about Christmas Shopping (Category: Economy):

- Where do you personally prefer to buy your Christmas presents?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of shopping on the internet?

- What is better: giving or receiving gifts? Why?

All questions were written by hand and checked for grammatical correctness afterwards. At the same time, exactly the latter turned out to be the main difficulty we encountered while working with the texts, as well as in the process of subsequent compilation of questions because many of us are non-native English speakers. Overall, all the obtained materials are considered suitable for English learners with different interests and to allow the exchange of different opinions.

Completion Metrics

The goal of the discussion task is to motivate users to converse and produce sentences around certain topics, to use grammar and vocabulary as well as to express their opinions in the second language they are learning (English, in this case). Here, the goal is primarily to make a clear, understandable conversation and be able to understand what others say and express one’s own opinion, while also paying attention to basic grammatical rules, and thus become more proficient in expressing oneself in the second language. So, in short, language comprehension and expression are the goals of the discussion task.

With these goals in mind, and since the users’ contributions in this task compared to the previous two tasks are less quantifiable, we needed to define a set of metrics to decide when the task is done and whether it is done successfully or not. In addition, the time during which each topic question is discussed is limited. This way, the task is more manageable and motivates the users to participate within a limited time frame. In the previous versions of the application, the completion metrics were rather quantitative: they were based on the number of words each player contributed, as well as the players’ own assessment of the quality of the discussion, captured via a poll. However, during the third semester, we decided to update the completion metrics to be more advantageous to the users from a learning experience perspective, and to add a qualitative aspect to the evaluation of the discussion.

Therefore, for the updated completion metrics of this task, we decided to combine quantitative and qualitative elements. More specifically, we compute two scores which serve as the basis for deciding if the task was passed, and if so, how successfully. On the one hand, individual user scores are computed based on the length and the grammatical quality of each user’s contributions in each question. In order to pass the task, each user needs to reach at least a certain score in two out of the three discussion questions. On the other hand, a group score is computed, requiring the entire group to reach at least a certain minimal grammar score, reflecting the quality of the contributions in relation to the overall quantity. If the two criteria are met, the group passes the task. Furthermore, in order to improve the learning experience of the task, users receive intermediate feedback during the discussion regarding their participation and performance in general. They also receive more detailed grammatical feedback at the end of the task. To match the storytelling framework, we also define three qualitative levels at which the users can pass the task, depending on their group score: an intermediate, a good, and a very good level. Depending on the level, the users receive different story continuations. For more details on how these two components of the overall completion metric are motivated, defined and computed, please visit the Grammatical error correction section.

Outlook

We think that the discussion task is a nice addition to the first two tasks. This could even be further developed in the future.

Possible future extensions of the task can include messages from the bot to discuss with users. An advantage of these contributions to the discussion can be more guidance and the effect of “model answers” which can serve for less experienced English speakers as an orientation. This also includes examples for the use of discussion phrases which can add to the learning effect.

Another additional feature can be corrections and helpful hints by the bot. Meanwhile, the bot should be similar as Barson (1993) describes the teacher in a similar classroom setting: only play a supportive role and help discreetly to identify errors while mostly appreciating the learner’s contributions.

Furthermore, vocabulary hints and short descriptions of words which are possibly new to the learners would be a valuable addition. This way probably an even bigger vocabulary learning effect could be achieved.

Implementation process

Here, we present the technical details of the implementation of this task. As part of our overall bot architecture, the implementation of the discussion task also relies on general modules like the Task(ABC) class and the room handler, described in the implementation section. Therefore, only the discussion-specific task handler is described here in detail.

Discussion(Task) is a subclass of Task(ABC). However, unlike the sentence correction and the vocabulary guessing tasks, the discussion task is not sequential in nature and, therefore, does not inherit from SequentialTask. Nevertheless, we were still able to reuse a significant part of the methods already implemented in said class.

The task always starts off with the presentation of the text, which is retrieved from the database based on the users’ proficiency. This is followed by three rounds of discussion.

At the start of each round, a text-related question is sent and a timer is added to the job queue to determine when the round finishes, such that visual reminders can be sent at regular time intervals to remind users to finish their discussion of the question on time.

Unlike other tasks, in this case we don’t have to select a specific user. Therefore, all user input can be handled in the same handle_question state. Word counts and grammar scores for each user are stored in two dictionaries, which are required to satisfy the completion criteria of the task.

After a message is sent, update_word_counts(message, user) and grammar_classifier.classify(sentence) are called in the evaluate_user_input(update.message.from_user.username, update.message.text, task_no=1) function. They are called on tokenized and preprocessed input in order to update those dictionaries with the relevant information.

In the first and the second discussion rounds, additionally to evaluating user input, the send_intermediate_feedback() function is called.

In the third and final discussion round, instead of intermediate feedback the final grammatical feedback is presented via calling send_final_feedback().

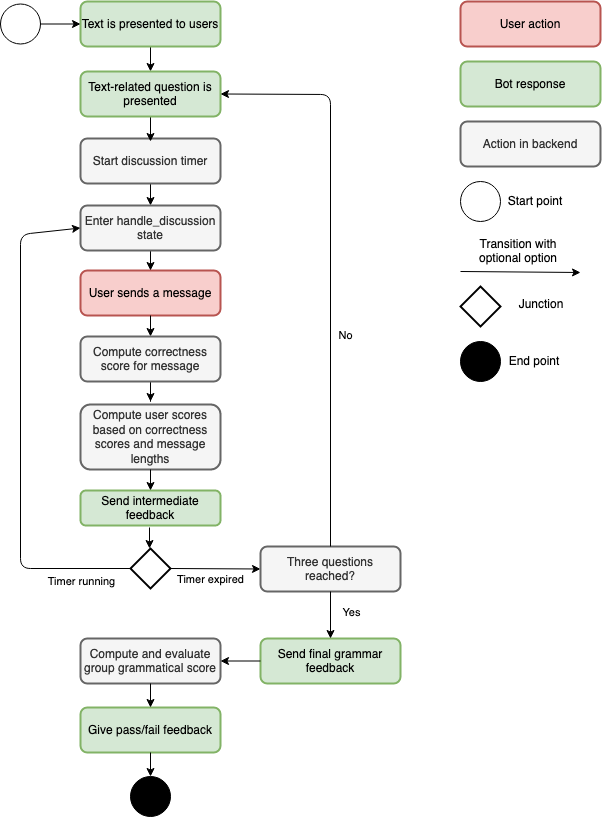

Finally, the dictionaries with the user information are passed to the is_correct(self) method to determine whether the task was successfully completed or not, and if so, at which level. Figure 3 shows a flow chart of the task up until the point where the users’ have to input the code and choose the subsequent task.

Figure 3: Flow of the discussion task including backend activities

References

Barson, J., Frommer, J. & Schwartz, M. (1993). Foreign Language Learning Using E-Mail in a Task-Oriented Perspective: Interuniversity Experiments in Communication and Collaboration. Journal of Education and Technology, 2 (4), 565-584.

Beauvois, M. H. (1992). Computer-Assisted Classroom Discussion in the Foreign Language Classroom: Conversation in Slow Motion. Foreign Language Annals, 25(5), 455–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1992.tb01128.x

Finn, A. N., & Schrodt, P. (2016). Teacher discussion facilitation: a new measure and its associations with students’ perceived understanding, interest, and engagement. Communication Education, 65(4), 445–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2016.1202997

Han, E. (2007). Academic Discussion Tasks: A Study of EFL Students’ Perspectives. Asian EFL Journal, 9(1), 8–21.

Jin, G. (2008). Application of Communicative Approach in College English Teaching. Asian Social Science, 4 (4), 81-85.

Kelm, O. (1992). The use of synchronous computer networks in second language instruction: A preliminary report. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 441–454.

Kern, R. (1995). Restructuring classroom interaction with networked computers: Effects on quantity and characteristics of language production. Modern Language Journal, 79, 457–476.

Lyster, R. (2018). Content-Based Language Teaching. New York: Routledge.

Murphy, S. (2013). Assessing text difficulty for students. In: What Works? Research into Practices. Ontario.

Oliva, M., & Pollastrini, Y. (1995). Internet Resources and Second Language Acquisition: An Evaluation of Virtual Immersion. Foreign Language Annals, 28(4), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1995.tb00828.x

Puspitasari, E. (2016). Classroom Activities in Content and Language Integrated Learning. Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Learning, 1(2), 1-13. doi:https://doi.org/10.18196/ftl.129

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in Thinking: Cognitive Development in Social Context. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sternberg, R. J.(1987): Most Vocabulary is Learned From Context. In: M. G. McKeown & M. E. Curtis (Eds.) The Nature of Vocabulary Acquisition (pp. 89-106). New York, London: Psychology Press.

Sullivan, N. & Pratt, E. (1996). A Comparative Study of Two ESL Writing Environments: A Computer-Assisted Classroom and a Traditional Oral Classroom. System: An International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics, 24(4), 491-501.

Warschauer, M. (1996). Comparing face-to-face and electronic discussion in the second language classroom. CALICO Journal 13(2), 7-26.