Listening task

Learn more about the listening task.

Contents

- Inline-Keyboards

- Access to the Audio-files

- Possible Exploitations

Motivation

The first three tasks have been designed to provide practice with core language skills concerned with literacy – the ability to read, write and construct sentences in a foreign language. However, as Renukadevi (2014) suggests, complete language proficiency depends crucially on another skill, namely listening. Being able to comprehend spoken words is necessary for face-to-face communication, which is the most common end goal of studying a foreign language (e. g., Morley, 2001). Not only is it necessary in order to come up with an appropriate response, but, importantly, it also helps students to acquire the correct pronunciation, word stress and a more confident use of vocabulary and syntax, which all improve the students’ speaking competencies. Yildirim and Yildirim (2016) as well as others have pointed out that ever since school curricula have transferred to a more communicative approach of foreign language teaching, listening skills have also been gaining in popularity in school environments. For this reason, we decided to create an additional task that can provide users with practice and more exposure to spoken English.

According to Gilakjani and Sabouri (2016), some of the most common issues for students with listening tasks are: quality of the materials, cultural differences, accent, unfamiliar vocabulary, as well as speed and length of the audio input. In order to make the learning experience meaningful for the users, we have taken these into consideration in our data preparation and more details can be found in the Materials section below.

Task Flow

Simultaneously listening to and comprehending information that is being presented is one of the most challenging parts when it comes to learning a foreign language. Listening is usually considered to be more difficult than grammar or discussion tasks, previously designed by us in this application. Since a single escape mission with three already implemented tasks already seems to be time intensive as well as requires perseverance, it was decided to make the new listening task voluntary. Participants are not obliged to do the listening but are given a choice after successfully finishing the main part of the game. Thus, this new task was in the first place meant for the most motivated students. However, in order to encourage users doing this task, it was decided to include it in a storyline in such a way, that in case of a successful completion of the task a new story content would be unlocked. Users will see a story block with them saving Elias and setting him free.

In the following, the description of the task flow will be presented in more detail.

In case users choose to perform a listening task, they are at first presented with the instructions of what they are expected to do in the following task session. Then, an audio file will be sent to the users so that they can prepare for the upcoming questions. Thus, participants are able to start listening to a clip before actually seeing the related questions (the reasoning for this will be explained further below). All audio files lay within the same time range of one minute, so that the game experience is fair for all participating groups. After the audio clip was sent in the chat, the first question together with the three possible answers will be presented to the participants. The chatbot also sends the name of a random player who is selected to designate the group’s final choice. Players are given 90 seconds to reflect on the question. They are not prohibited from revisiting the audio clip during this time. Players can either use all the 90 seconds for preparation or answer before the indicated amount of time has elapsed. After the selected player states their answer, the next question is shown in the chat. The same procedure applies to all questions. In total, each audio clip is assigned four different questions, three of which are being randomly sampled and presented during each game run.

Because Telegram was chosen as a platform for the application, we have encountered a series of difficulties while designing this task. First of all, in the typical classroom scenario the list of questions is presented to the students before the audio task, with an audio clip usually being played twice. In case of Telegram, it is impossible to control the amount of times users get exposed to the audio, since we did not manage to come up with a tool that can get the audio file deleted from the chat. (This can be done depending on 2 conditions. For example, after a certain amount of times the audio was played. Or after a certain amount of time that has passed since the file was sent to the players.) Thus, a new scenario had to be created in such a way, that it both satisfies the learning goals of improving the users’ listening skills and seems to be suitable for its implementation in Telegram. Hence, we concluded that presenting the audio before the questions was the most suitable solution implementation-wise as well as the means to get players interested in the task and better engaged.

Materials

At the moment, the audio database contains 45 recordings, each centered around a certain topic and labelled according to a difficulty level. All files come from publicly available websites which are intended for learners and teachers of English as a foreign language, namely www.listenaminute.com, www.elllo.org and www.esl-lounge.com. We made sure that all sources legally allow the use of their audio materials for non-commercial purposes.

The users should be familiar with a task of answering questions related to the heard materials, as this methodology is often used in language learning courses. However, in order to create an experience that resembles the real world rather than a test environment, the users find out the questions after, not before listening. In such cases it can be challenging to catch every detail at first attempt, so we decided to allow them to self-regulate the number of repetitions.

Along these lines, to keep the overall length of the task to an appropriate time window even if the users decide to listen multiple times, we decided to standardize the length of every audio file to approximately one minute. Files of such length are also going to be much easier on the device memory storage of the users, which is certainly an added plus.

In order to provide a more authentic learning experience, we aimed to provide a good variety of speakers with regard to their voices and accents, as well as a wide range of everyday topics, for which intermediate learners are expected to have the required core vocabulary. Some examples include Health, Media, French Fries and Job Duties. Unfamiliar accents can severely hinder students’ abilities to understand the spoken words (Gilakjani & Sabouri, 2016), so only speakers of the most common native English accents are included in the final data set.

Since the maximum number of players is four, we have designed four questions per audio, each with three possible options to choose from where exactly one is correct. The focus of the questions is also diverse. Some require a general understanding of the speaker’s attitude about the topic, others ask for a more detail-oriented listening or distinguishing between homonyms (equally or similarly sounding words) based on context.

In terms of the difficulty level, the main motivation for the division was to eventually accommodate the adaptive module, which assigns a specific question to the users based on their previous performance. There does not seem to be a unified official method for determining the difficulty level of a listening task. Therefore, our process was as follows: the content (in form of a textual transcript) was first evaluated based on the language complexity and vocabulary using a combination of automatic tools (1, 2) to indicate a CEFR level [3] of a text. In addition to this indication, the data was also subjectively evaluated for speech qualities such as tempo and clarity, and the final level of difficulty resulted from agreement between three judges.

Although our target audience is mainly B1-B2 students, since the intermediate proficiency group tends to be quite heterogeneous in terms of the individuals’ strengths and weaknesses, we also included slightly simpler audios that could theoretically be used with motivated A2 students, too.

Each recording was carefully reviewed by at least three people, checking for the sound quality of the recording, correctness of the language and multiple choice questions, flagging potentially sensitive subjects or unsuitable language, and as mentioned, checking the indicated level of difficulty.

Implementation

In the following we will describe how the suggested task flow is achieved from a technical point of view.

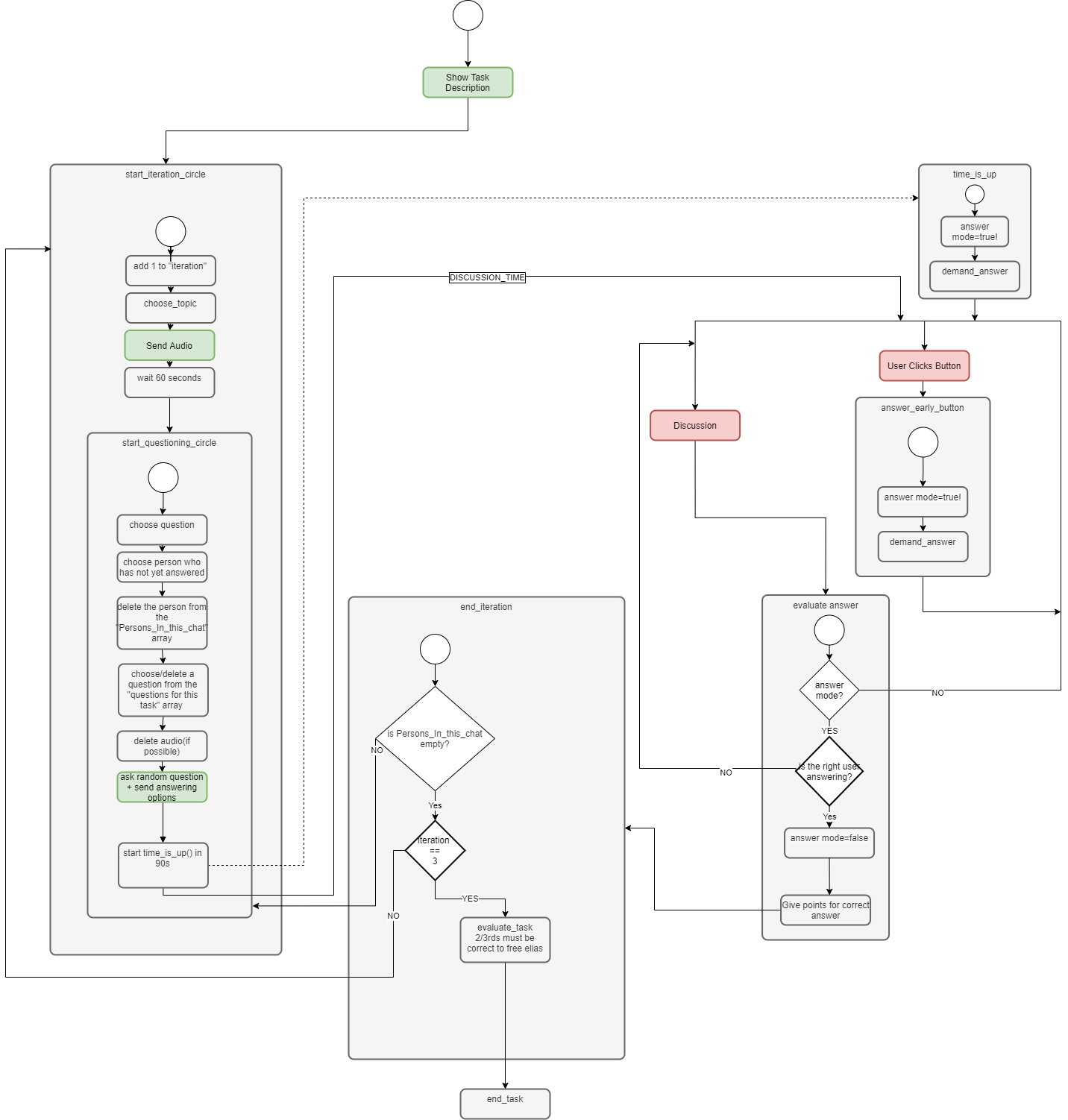

The task consists of two loops that wrap the answering function. The first loop is the “Iteration-Loop”. In there the topic of the next audio file is selected and the matching audio file is sent, using the newly implemented send_audio-function. After sending the file, the questioning-loop is started. In there a question, regarding the audio file, is selected from a group of up to 4 different questions. Additional to that, the answering options are presented, and a user is announced who is supposed to answer. Now the users have 90 seconds to discuss the given answering options. To check for these 90 seconds, the function time_is_up() is being called to be executed in 90 seconds. If they have found a solution earlier, they can additionally press a button in the previous message, to skip their discussion time. Since the time_is_up() function is called only after a certain period of time has passed, it can not return anyhing and therefore can not change the state. This is resolved by adding a second type of state: the answer-mode. Whether a group is in answer-mode is saved in the instance of the task. While the answer-mode is deactivated all the chat-messages are still reaching the evaluate_answer()-function, but they are not evaluated, but discarded as part of the discussion. If either the time_is_up()-function is called or the button is pressed, the answer-mode is activated. This causes the bot to evaluate the next answer which is given by the earlier announced user. After the user gives the answer, the answer-mode is deactivated again. If the answer is correct the group gets a point. Otherwise, they do not. This process is repeated until each user in the group had one question regarding this topic. This closes the questioning-loop. If the questioning-loop is completed a new topic begins and a new iteration begins. The complete task consists of three iterations. If they were able to collect more than two thirds of the points, they were successful. To get a better overview over the flow of the task have a look at figure one.

Figure 1: Flow-Diagram for the listening task

Inline-Keyboards

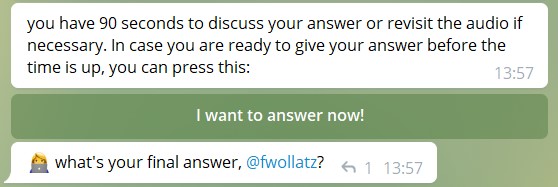

Since the users are allowed to discuss for 90 seconds, but additionaly are allowed to answer earlier, we had to think of a possibility to either change the state after an appropriate amount of time, or to allow the users to induce this change of state. Therefore we decided to use the so called Inline-Keyboards. In this particular case it is used in the form of a button that says “I want to answer now”. When the button is pressed a CallbackQueryHandler is called, which in turn calls the time_is_up function. This function sends out the answering options and thereby stops the discussion. A picture of the Inline-Keyboard can be seen in Figure two.

Figure 2: Example of the inline-keyboard used for this task

Access to the Audio-files

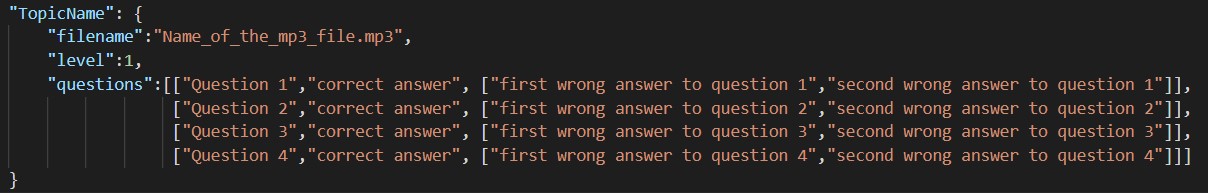

To give the design team easier access to the questions a decision was made to collect the different topics in a json-file. The file consisted of multiple topics, which followed the structure, as can be seen in the image below. One Topic contained the filename of the mp3 that gets played, the proficiency level needed, as well as four or more questions and their answers.

Figure 3: Example of the inline-keyboard used for this task

Possible Exploitations

There are two possible exploitations in this task. The first being that anyone in the group could press the “I want to answer now”-Button, not only the one who is supposed to answer. This could lead to pressure from the other students and cutting short the discussion time. The second possible Exploitation is, that, after the time runs out or the button is pressed, the game waits for the answer of the player who got selected. This is not timed in any way, which could potentially lead to the user waiting forever until he answers. In addition to that, all other students can still write, potentially giving tips, even after the 90 seconds.

These two problems could not be solved completely, due to time constraints and the shortage of manpower for the implementation of the task.

The first problem could be solved by checking who clicked the button and only calling the time_is_up-function when the right player clicks.

The second problem could be addressed by implementing a second timer, which counts down from ten.

References

[1] http://www.roadtogrammar.com/textanalysis/ (accessed 29.06.21)

[2] https://cefr.duolingo.com (accessed 29.06.21)

[3] Council of Europe (2020), Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, available at www.coe.int/lang-cefr

Gilakjani, A. P., & Sabouri, N. B. (2016). Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review. English language teaching, 9(6), 123-133.

Morley, J. (2001). Aural Comprehension Instruction: Principles and Practices. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language (pp. 69-85) Boston: Heinle and Heinle.

Renukadevi, D. (2014). The role of listening in language acquisition; the challenges & strategies in teaching listening. International journal of education and information studies, 4(1), 59-63.

Yildirim, S., & Yildirim, Ö. (2016). The importance of listening in language learning and listening comprehension problems experienced by language learners: A literature review. Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 16(4).